The very first John Wick movie came as a breath of fresh air during a time when action films were becoming increasingly unimaginative. Many agree that the movie totally saved the Hollywood action genre when it was released in 2014. The movie brought the reserved and confident presence of Keanu Reeves to a stripped-down plot, and enamored audiences with a new and elaborate action style. Yes, John Wick went through hordes of mercenaries like in a video game. However, the sense of technical proficiency with which the character treated his guns gave a special thrill to movie-goers.

It instantly made lifelong fans among cinephiles and was dubbed a cult classic just a week after its release. The pieces that went into this reinvention of the Hollywood action genre were a chain of influences that started with the gory crime flicks of Hong Kong filmmaker John Woo, and ended with Chad Stahelski, the stuntman-turned-director who helmed the movie. Underlying this major cinematic cultural exchange was an absurdly brilliant genre of action known as Gun Fu.

Birth in Hong Kong Crime Action Flicks

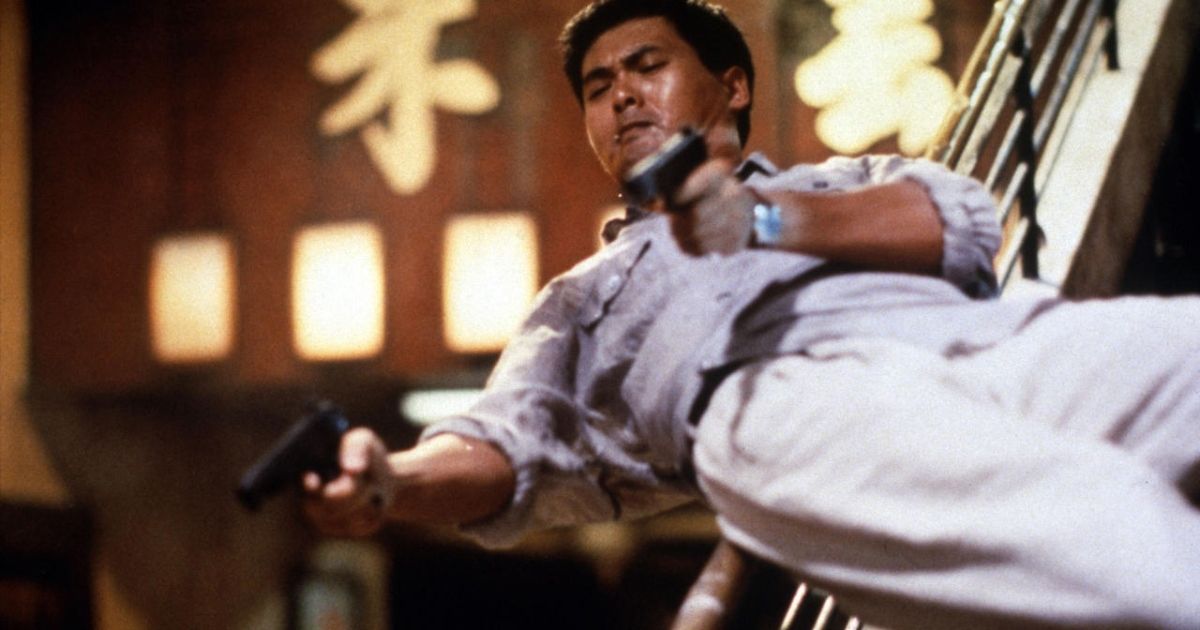

The birth of Gun Fu is widely attributed to one single filmmaker — John Woo. Hailing from Hong Kong, he found his start in the 70s within the same filmmaking industry that gave rise to Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, even working with the latter on some films. Woo began his filmmaking journey with kung fu movies, which were basically the Westerns of Chinese cinema, minus the traditional shootouts. In popularity and abundance, they rivaled that of Western movies in America, but they were an insulated genre of action with vast stylistic differences. Guns were little more than props in kung fu movies, and the action was based on elaborate hand-to-hand combat sequences that bordered on graceful.

Meanwhile, gunfights were the bread-and-butter of action in Hollywood cinema. Western films basically set the original standard for shootouts in Hollywood films. These films also posed a far different set of values in the action hero. Gunfights in the cinematic Wild West often gave the best advantage to the quickest draw, and their heroes were often the most prodigal in this skill. This meant that action in Hollywood films was relatively stationary; there were no chaotic brawls that had characters scuffling all over the screen.

Working in the Hong Kong film industry, John Woo was equally impressed with the dance-like acrobatics of kung fu as he was with the Mexican standoffs of cowboy Westerns. Later in the 80s, he began to conceptualize a whole new style of action films that sought to marry Western gunfights with the cinematic conventions of his own genre. The result was a gory, high-octane style of action cinema that came to be known as heroic bloodshed films.

In making these films, Woo basically combined the intense physicality of kung fu with the gratuitous gunfights of the Western. Heroic bloodshed films were set in a world of crime, with protagonists who were either cops or criminal enforcers themselves. They would often walk into the enemy’s lair with guns blazing, and these battles would regularly end up in close quarters with more guns firing than you could count. The Killer, A Better Tomorrow, and Hard Boiled were some of the important titles that saw the development of this new genre of action. Hard Boiled even featured probably the earliest form of the hallway fight — years before The Raid.

The Hollywood Filmmakers’ Fan Club

The unique style of cinematic action invented by Woo quickly found fans in the West. And in 1999, The Matrix created the first meaningful blend of Gun Fu with Hollywood action. The Wachowskis, who created the movie, were major fans of Chinese kung fu movies, and of John Woo in particular. They understood the charm of both, and sought to recreate it in their own movie.

For this, they imported top talent from the source. Yuen Woo-ping has had a serious role in Hong Kong’s kung fu cinema, directing many important movies such as Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow. With him as the fight choreographer, The Matrix saw its leading actors accomplish impossible feats of acrobatics. There was a special focus on the aesthetic of the action — an important aspect of kung fu cinema. These sequences also had an undue amount of blaring gunfire, which too were portrayed with special care for cinematic beauty.

Of course, the movie had one crucial difference from John Woo’s films — it took itself too seriously. Woo started his career in a film industry where comedy and kung fu were the two most prominent genres of films. His groundbreaking films such as The Killer reflected this attitude, maintaining a charm despite the silliness. On the other hand, The Matrix framed its outrageous action as surreal rather than silly. It worked, and a truly unique and inimitable film was born.

But this artistic divergence was evidence of a core difference between the filmmaking sensibilities of Chinese kung fu and American blockbusters. While the dance-like elegance and a comedic lilt were essential to making a kung fu movie feel at home, serious action was the only way to sell tickets to Americans. The Matrix hit the nail right on the head; within a few years of its release, Hollywood filmmakers were trying to understand their newfound preferences for action cinema with groundbreaking new releases. The Bourne Identity sought out a stark realism combined with an extremely competent protagonist, making way for eye-catching action sequences through this combination. Collateral was an action drama in which firefights demonstrated elite real-world practices that awed the audiences.

Gun Fu Goes Super Saiyan

The directors of John Wick, Chad Stahelski and David Leitch, were there to see the Hollywood side of things start out in real time. They were stunt doubles for Reeves in the first Matrix movie, with Stahelski working as stunt coordinator for the sequels. A lengthy history working as stuntmen and stunt coordinators made them the perfect minds to give shape to the John Wick universe.

The duo also had some striking ideas about how action should be crafted on screen. Talking to That Shelf, Leitch spoke about the importance of realism to shoot better action scenes.

“Martial arts has become such a mainstream thing now that you can’t fake that kind of thing. There will always be someone now watching a fight scene that knows how they work, and they’ll be thinking, “I don’t know if I would do it that way.” So it’s nice to infuse martial arts that people can actually do, that’s appropriate to the situation, that’s done properly, and to have a cast that would be willing to go through the training to make it seem real. They can reload and fire a firearm. They can operate vehicles and do the proper maneuvers.”

Armed with these beliefs, as well as the unending trust of the leading man, Keanu Reeves started an intense period of physical training for John Wick that lasted for four months. During this period, he learned judo, jiu-jitsu, and even 3-gun training with real firearms.

Behind the scenes, Stahelski and Leitch were busy crafting a brand-new style of fighting for the screen — something that combined real grappling techniques with realistic firearm practices so that they flowed seamlessly from one to the other. The real training in fighting styles, as well as hours spent doing 3-gun drills, allowed Reeves to execute numerous permutations of grapple, slam, and shoot that became the epitome of Gun Fu. His real-life proficiency in the fighting arts meant that the directors were free of the ban of the shaky camera, and the fast cuts. Action sequences could be portrayed head-on, allowing for better focus on other cinematographic elements that would enhance the storytelling.

Reeves’ experience with using real guns also allowed him to bring in a truly realistic portrayal of gun usage — one that simultaneously communicates vigilance and careless mastery. This hypnotic tone is present in pretty much every action sequence of the John Wick films, and it is what thrills the viewer about the movies’ distinctive action style, Gun Fu.