John Lennon was killed giving an autograph. Remember that.

The mononymous singer Selena, who's sold 18 million albums, was only 23 when she was shot and killed by the founder and president of her fan club. Pantera guitarist Dimebag Darrell was shot and killed at the age of 38 by a fan who accused him of breaking up the band. The up-and-coming singer Christina Grimmie, a contestant on The Voice who hit four million subscribers on YouTube, was shot and killed by an infatuated fan obsessed with the young artist. On dark days, it seems like every vocal online 'fan' is auditioning for the part of Mark David Chapman.

Has the internet ushered in a new age of democracy, or toxic fandom? The question almost seems too obvious to ask — one need only look at the countless artists and celebrities who've had to delete their social media to avoid the onslaught of harassment targeted their way; one need only take a stroll down the hate-spewed hallways of Twitter or the chaotic corridors of comment sections for misanthropy to swell, victorious yet again over any seemingly antiquated 'faith in the human race.' But what does this say about art? What does this say about democracy itself? And what does it actually mean to be a fan?

The Nature of Fans

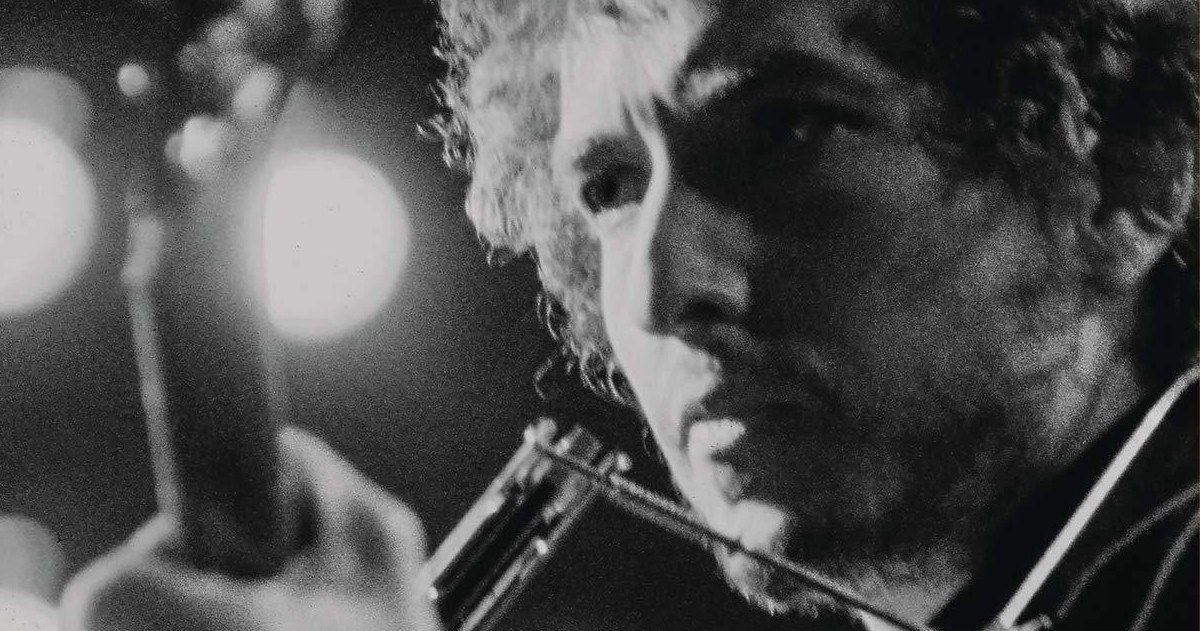

"Why is it that when people talk about me, they have to go crazy? What the f*ck is the matter with them?" Bob Dylan asked rhetorically in an interview with Rolling Stone, discussing the nature of fans. He continues:

They want to know what can’t be known. They are searching – they are seekers [...] For what? Why are they doing this? They don’t really know. It’s sad. It really is. May the Lord have mercy on them. They are lost souls. They really don’t know.

Before dissecting the nature of fandom today, it might be helpful to understand what exactly a fan is; or, perhaps more importantly, why someone is a fan. There's a spectrum of fandom, and it's somewhat reminiscent of substance use disorder. Just as there are people who can drink socially or use recreational drugs in a way which does not destroy their lives, there are individuals who look forward to upcoming Star Wars movies or shows, but their involvement in the franchise doesn't interrupt their daily lives; these are functioning fans.

Alternatively, there are individuals who watch a Star Wars series like Obi-Wan Kenobi and then go out of their way to spew insults and hatred toward actor Moses Ingram, someone whom they have never met in their life but are now suddenly attacking as if she poisoned their pet; these are toxic fans, the equivalent to someone robbing a pharmacy for their opiate addiction. In short, as Rick and Morty co-creator Dan Harmon said when expressing his shame at the fans of his show, "These knobs that want to protect the content they think they own [...] I’ve made no bones about the fact that I loathe these people. It fu*king sucks."

Fans Favor Fiction

By definition, there's a warping of reality involved for any fan, since fandom inherently focuses on the artifice of fabricated fiction over objective reality (or at least what can be commonly agreed upon ontologically as 'reality'). A degree of fantasy can certainly be healthy in life, but serious fans have had their reality so obliterated that it seems perfectly rational to attack and berate strangers who disagree with them or who 'contaminate' the fiction they enjoy. This is the equivalent of punching someone because they kicked your imaginary friend.

What is it about fiction which gets us to ditch life? Perhaps Dylan is right, and fans are 'seekers' — the lost ones incessantly searching for something better than the hand they've been dealt; the people who'd rather dwell in make-believe than make their beliefs a reality; the nine-to-five adults whose inner child has imprisoned their maturity; the ones so desperate for meaning and connection that they'd fly around the world to experience a better fiction rather than go nextdoor to live a humdrum truth. Maybe it is sad to be a true fan, a yearning soul incapable of enjoying a piece of entertainment and simply moving on, and instead haunting the very thing you love until it haunts you.

'It's difficult to separate the artist from the art,' people say, but doubly so for a fan. We've heard this saying a lot recently, as countless allegations are made against various artists, and their fans have had to reckon with the shows and films they love having been made by monsters masquerading as men and women.

People who grew up loving The Cosby Show, for instance, have found a deep need to talk about Cosby as a horribly flawed and unethical man who is markedly different from the positive and inspiring art he helped create. But the phrase 'separate the artist from the art' applies to fans in another way.

It's Not Them, It's You

Fans have a notoriously difficult time separating the artist from the art. Perhaps the biggest place we see this is in casting. As fans immerse themselves in the world of their beloved fictions, the discernable lines between actor and role blurs, and the person cast is correlated with the fictional character.

When fans believed that the previously beloved Chris Pratt attended a supposedly homophobic church, they aggressively petitioned to recast his character Peter Quill (or calling for character Kitty Pryde to replace him). There have been countless calls to replace Amber Heard in Aquaman 2 after her trial with Johnny Depp. The performance itself seems to matter less than the person playing the character, and the resentment often says much more about the bitter fans than it does the performer unaware of their existence.

The opposite side of this, in which fans really love the actors and artists involved in their fandom, is equally toxic. Parasocial relationships are the one-way street of fandom, in which someone projects emotions and ideas onto a person they've never actually met, simply because they are fans of the person. Countless fans claim to know 'the real' celebrity, and have developed unhealthy parasocial relationships with performers who neither have nor will know they exist. "People listen to my songs and they must think I’m a certain type of way," Dylan goes on to say in the aforementioned interview. The fact is, all that fans know are screens, and when the screen is turned off, everyone is faced with their own dark and lonely reflection.

How Fans Change Art

Corporations like fans; artists usually don't. This is why massive film distributors and studio executives will poll audiences and companies will algorithmically track the social media interactions of fans (who are always reduced to being consumers), whereas most actual celebrities would rather gouge their own eyes out than spend a day with one of their fans. Fans have always influenced the entertainment industry. Test screenings and audience polls have had significant effects on films for decades. Sometimes this can be harmless and humorous, like the title of the James Bond movie Licence to Kill existing as the result of American audiences' distaste for the original title, Licence Revoked, because it reminded them of the DMV.

The problem is, there is no one, monolithic 'audience' of fans, because individuals have different tastes. Listening and caving in to fans' reactions every time will likely be a losing battle of infinite adjustments, because there are so many conflicting opinions. Take, for example, Justice League. Warner Bros. changed Zack Snyder's version considerably after various incidents, including extremely negative reactions to Snyder's Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Of course, there were negative reactions to the Warner Bros. changes as well, leading to immense pressure for Snyder's original cut of Justice League to be released.

Some will say that this kind of power is a positive progression; after all, isn't the art 'for the fans?' Is it though, and where does it end? Fans have changed the animation design for Sonic the Hedgehog, prevented Michael Bay from ret-conning the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles as aliens, turned Apocalypse blue instead of purple in X-Men: Apocalypse, 're-Asianed' Ghost in the Shell, reshaped the aesthetics of Will Smith's genie in Aladdin, and much more.

Even the playfully ironic trolls behind Morbin' Time have driven the much-despised film Morbius' return to theaters (on 1,000 screens, no less), and might even be memeing a sequel into existence that no one wants (at least unironically). Even legendary director Ridley Scott isn't immune to the wrath of fans, feeling pressured to add more Xenomorphs into the Alien franchise after responses to Prometheus, telling Yahoo! News:

What changed was the reaction to ‘Prometheus,’ which was a pretty good ground zero reaction. It went straight up there, and we discovered from it that [the fans] were really frustrated. They wanted to see more of the original [monster] and I thought he was definitely cooked, with an orange in his mouth. So I thought: ‘Wow, OK, I’m wrong’.

Imagine Picasso altering Guernica or Beethoven editing his ninth symphony because of the negative backlash of fans, and you might have some historical context for what's happening. Perhaps art shouldn't be democratic; maybe great art can only be an act of fascism. Otherwise, fans might kill what they love.

What Fans Tell Us About Democracy

The internet is an interesting thought experiment in democracy. What happens when everyone has a voice? Have we created a platform for diverse thought to dialectically further art, politics, justice, technology, and society, or just an echo chamber of Cheeto-crumbed mouths screaming incoherently into the cultural abyss? Can the internet, and democracy itself, be good when people aren't (or at least when the loudest of them aren't)?

The word 'democracy' stems from the Greek words for people (demos) and power (kratos), which is about as appropriate as etymology gets. But "with great power comes great responsibility," as comic book (and Winston Churchill) fans are well aware. Should everybody wield power? What happens when they do? Trump, Brexit, Morbius 2? This was essentially the foundation for the great debate over democracy, waged foremost by Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Rousseau believed in direct democracy because he believed in people; Hobbes, on the other hand, had a much less favorable view of humanity, writing, "When all the world is overcharged with inhabitants, then the last remedy of all is war, which provideth for every man, by victory or death." Essentially, the view of humanity put forth in his tome Leviathan is a grim one in which, if the world is ruled by the masses of selfish individuals, endless war is the only logical result.

Power to the People?

For Hobbes, giving 'power to the people' was truly dangerous. It's a safe bet that Hobbes wouldn't have changed his mind much, had he lived through our digital age. A pointed quote from Leviathan could very well be aimed at 'fans' and those hubristic denizens of online comment sections:

Such is the nature of men, that howsoever they may acknowledge many others to be more witty, or more eloquent, or more learned, yet they will hardly believe there be many so wise as themselves.

The greatest strength of democracy is the same as the internet's, namely the flattening of authority. But what happens in the vacuum of authority, when only the loudest voices get heard? For some, the result of all this is the death of truth. When everyone's voice has equal weight, just as much legitimacy is given to dangerous conspiracy theories and idiotic ideas antithetical to scientific fact as is given to well-researched and supported truths. Hate gets the same weight as love. Fiction becomes just as plausible as fact. To quote Hannah Arendt in her book The Origins of Totalitarianism:

The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.

The End of Fandom

This all brings us back to modern fandom. The onslaught of loud, angry voices, and even the genuine appeals of passionate fans, might just be annihilating art and truth (which are arguably often one and the same). Where is the distinction between reality and fiction when a fan gets apoplectically enraged over casting or script decisions in a franchise about superpowers or space warriors? How does art really benefit from the fan, and how do fans deserve their fiction? Perhaps the true fans are the ones who don't demand. Maybe it's time to get back to being audiences again, instead of fans.

Then again, even Bob Dylan took a fan tour of John Lennon's childhood home, back in 2009, nearly 30 years after Lennon's own "lost soul" of a fan killed him. However, at least Dylan had the quiet courtesy to attempt anonymity and go unnoticed.

.jpeg)

.jpg)