There are plenty of film lovers who would not consider the 1985 dystopian classic, Brazil, a science fiction film. One of them is the creative genius behind the film, writer and director Terry Gilliam. In a 2014 interview with the British Film Institute, he was asked how much science fiction played a part in his early life. Was he a science fiction fan?

Not really. Well, no, that’s not true. The ones that really got me going were like Kubrick, with 2001, the really intelligent ones that seemed to be talking about things. I wasn’t particularly interested in the monster ones; they tended to be silly.

What about those who consider his film Brazil a science fiction film?

I find it very odd that people think it should be in the science fiction section, because I don’t think it’s science fiction. At the time, it was more of a documentary, as far as I was concerned, about the world it seemed we were living in.

Is Brazil Sci-Fi?

Which is exactly why Brazil is such a brilliant filmmaking achievement, and one of the compelling reasons why it might just meet the criteria of great science fiction. To use Gilliam’s own words, the film is really intelligent, and seems to be talking about things, as good science fiction should. But on top of that, it features architecture and technology beyond time and ordinary imagination. That the style is extremely eclectic, and the story has no defining date only adds to the technological wonder, a quality essential to science fiction. Gilliam continued:

I was trying to make it in no place at all, neither future, nor past. A mixture. And there had been so many space films — I didn’t want it to look like that. So, it was trying to make it retro, so it could be taking place in the ‘50s, like Popular Science magazines [...] or later. It didn’t matter.

Add in a cold, dark, dystopian background and the result is a movie that can easily be compared to movies like Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey or Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, both intellectual science fiction masterpieces. But perhaps there’s an even stronger link that nudges Brazil into the nebulous realm of science fiction.

Great Science Fiction Is About Political Threats to Human Decency

Consider any list of the greatest science fiction movies of all time. Whether it’s a list of ten movies or a hundred, it’s difficult to find a film that isn’t built on a foundation of political concerns. The core conflict in almost all science fiction is a political threat to human decency. Let's examine this in four of the most appealing and popular science fiction stories of the past half century:

Star Wars

Perhaps the most popular science fiction universe ever has politics built right into its name. The “Wars” of Star Wars, of course, refers to the ever-present backstory of the fall of a galactic republic to a powerful emperor, which leads to a rebellion whose goal is to end tyranny and oppression. The many players — senators, Sith, Jedi, and clones — and their many tools — blasters, lightsabers, TIE fighters, and death stars — all come and go, but political purposes and intrigue drive every story from beginning to end. This was highlighted at its best in the recent Star Wars series Andor.

Dune

The founding fathers of science fiction might have set the tone of sci-fi movies by making their stories vehicles for social and political commentary. Frank Herbert’s universe of Dune explores the deep end of the political pool. It's a story that has Great Houses established on planets that jostle for prominence within the Imperium, which is ruled by military might and the strict control of interplanetary travel and economics, while factions with opposing philosophies secretly advance technology and genetics programs to increase their power and influence. The heroes and villains alike are caught in this complex, inescapable political web.

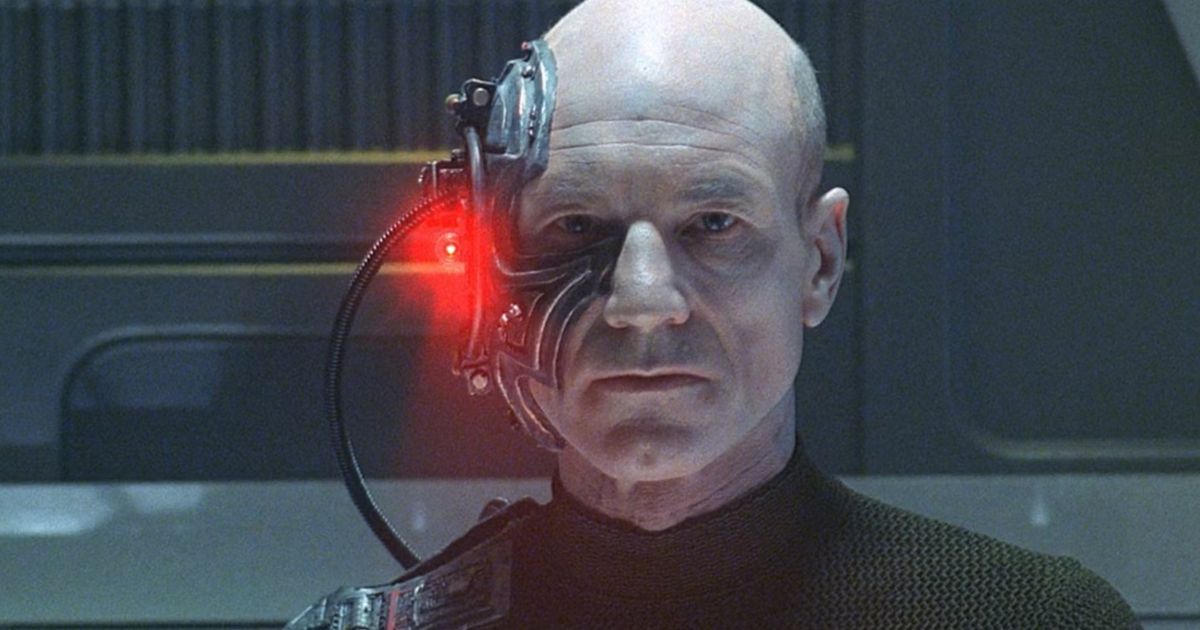

Star Trek

Of all the huge science fiction franchises, this is the universe that one would expect to leave political concerns behind for the sake of scientific exploration. Even the Federation’s prime directive seems to want to keep starships uninvolved. But the prime directive is itself a political mandate that repeatedly comes with its own set of troubles, and more stories than not revolve around humans, Klingons, Romulans, Cardassians, the Borg, the Dominion, the Xindi, the Breen, and Vidiians all trying to maintain or shift the balance of power in one quadrant or another.

Alien

Even the monster-based science fiction movies that Terry Gilliam might think of as silly are steeped in politics. The universe of Alien movies could have had stories that are all simple, apolitical thrillers, but that’s not the case. From the beginning, Ridley Scott’s 1979 thriller Alien is not just about the struggle to survive the monster that got on board, it’s also about why the monster is on board. The Company’s weapons division already knew what was on LV-426, and would do anything for control of the ultimate biological weapon. The crew is expendable in the face of profits and military might.

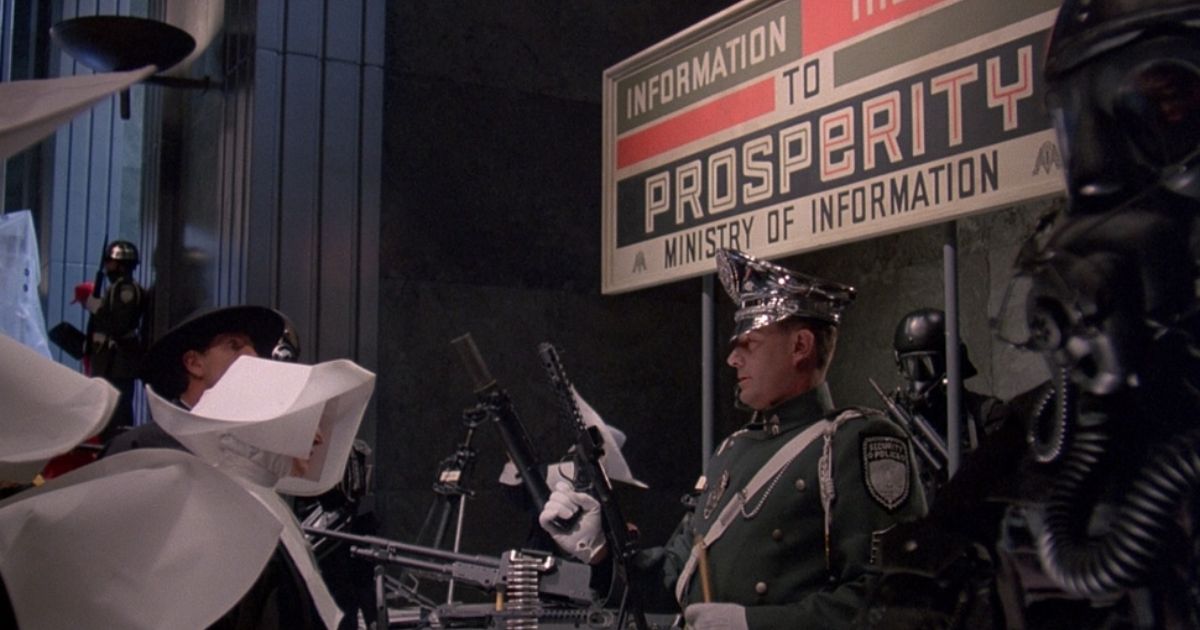

Brazil’s Extraordinary Social and Political Insight

Brazil does have elements of mainstream science fiction, things like an angelic suit of winged armor, or an exoskeletal device to enhance (or perhaps, control) finger dexterity while using a keyboard, or an intrusive security robot with a telescoping eye that prowls the halls of the Ministry of Information, among many other things. But it’s still a decidedly grounded movie. Flying only happens in dreams. There are no spacecrafts or beam weapons, no twin suns or planetary rings. And outside of dreams, there is nothing more inhuman than the very worst of humanity.

But as truly great science fiction often is, it might just be a prophetic (and terrifying) vision of where the human race could be headed. The place Brazil challenges reality is not in advanced technology or extraterrestrial biology: it warns of a coming world where every detail of human life is controlled by corporate and political bureaucracies. In such a world, information becomes a weapon that is used to punish whoever thinks the wrong thoughts or says the wrong things. As Gilliam points out in the aforementioned interview, there are real parallels to our world today:

Homeland Security is the Ministry of Information, and if you can’t find terrorists, you invent terrorists. If you listen into enough people’s conversation, you’ll probably find somebody who had a terroristic thought in their head for a moment.

Could our 21st century culture have arrived at this place of aggressive control already? Not just governmental security agencies, but in the corporate workplace? Are people being treated differently for what they believe, or for something they may have emailed or tweeted in their past, some piece of information that someone went to great trouble to dig up? It has to be admitted that social media has somehow become a war zone in our real world, and much of it revolves around demonizing those who are different.

The Depth of Brazil Is Astounding

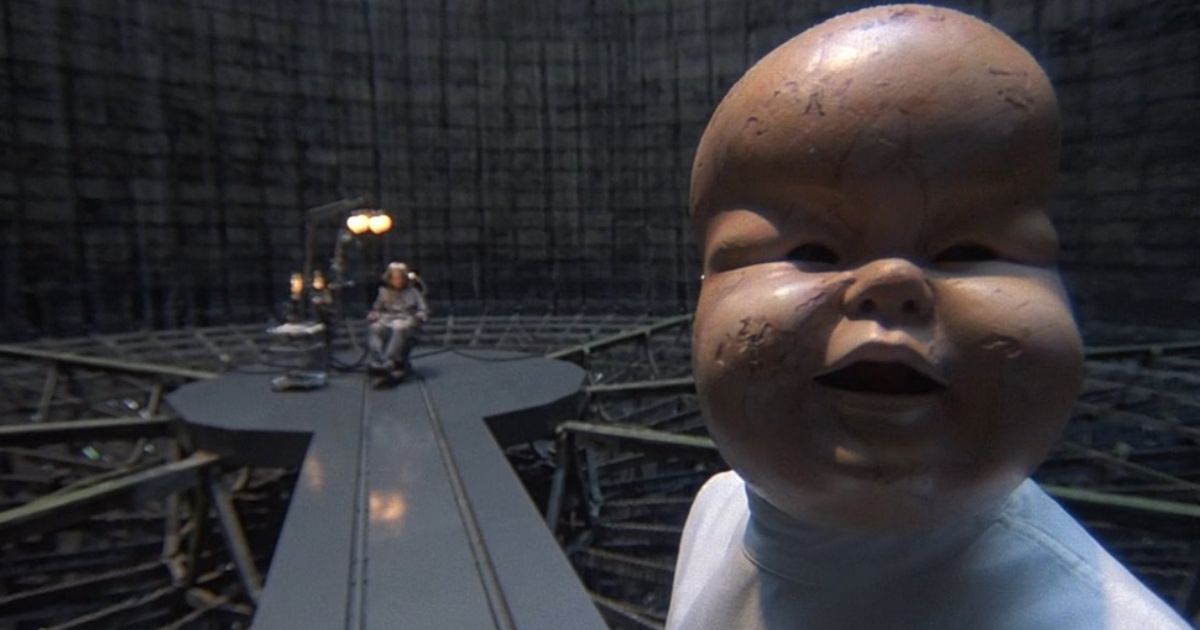

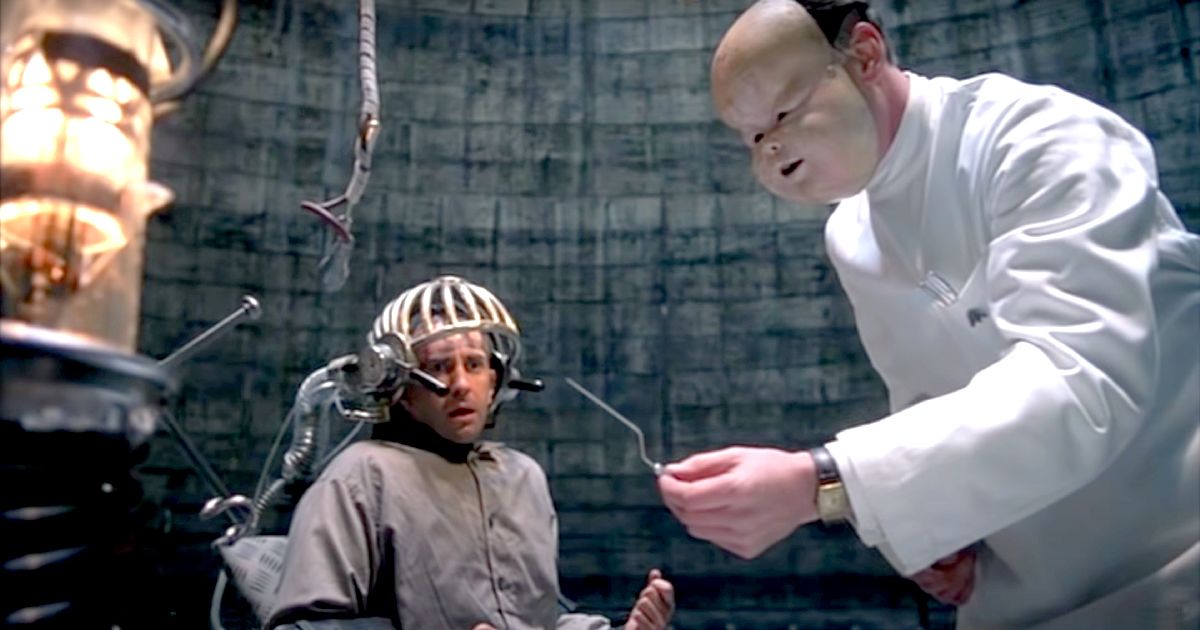

Brazil also has something to say about cultural values. A pivotal moment happens when the protagonist, Sam Lowry, who is absolutely not a terrorist by any reasonable definition, is arrested for being a terrorist. As he is strapped to an interrogation chair with instruments of torture all around, a compassionate armed guard whispers, “Don’t fight it, son. Confess quickly. If you hold out too long, you’ll jeopardize your credit rating.”

This is the kind of incredible satire one would expect from a member of Monty Python, and it’s hard not to laugh out loud, but it’s also one of the most telling lines in the film. In the context of a single breath, the most minor of characters communicates the nightmare inhumanity that can grow in systems of social control, the necessity of those having to support such systems to hide their humanity, the choice between compliance and harm that individuals who don’t keep in line have to face, and the system’s true measure of the values that everyone knowingly or unknowingly subscribes to, like eternal youth or credit ratings.

If Brazil can be considered science fiction, it should be considered one of the best sci-fi movies ever made. The design and direction of Terry Gilliam has produced a world unlike any other, and at the same time, something frighteningly and intimately familiar. The wonderful performances of Jonathan Pryce, Ian Holm, and Robert De Niro are brilliant, fun, tragic, and strangely heartwarming. And finally, the film’s disturbing vision of a cold, controlled life of social boundaries and stifling bureaucracy is a warning that should be taken seriously.

.jpg)