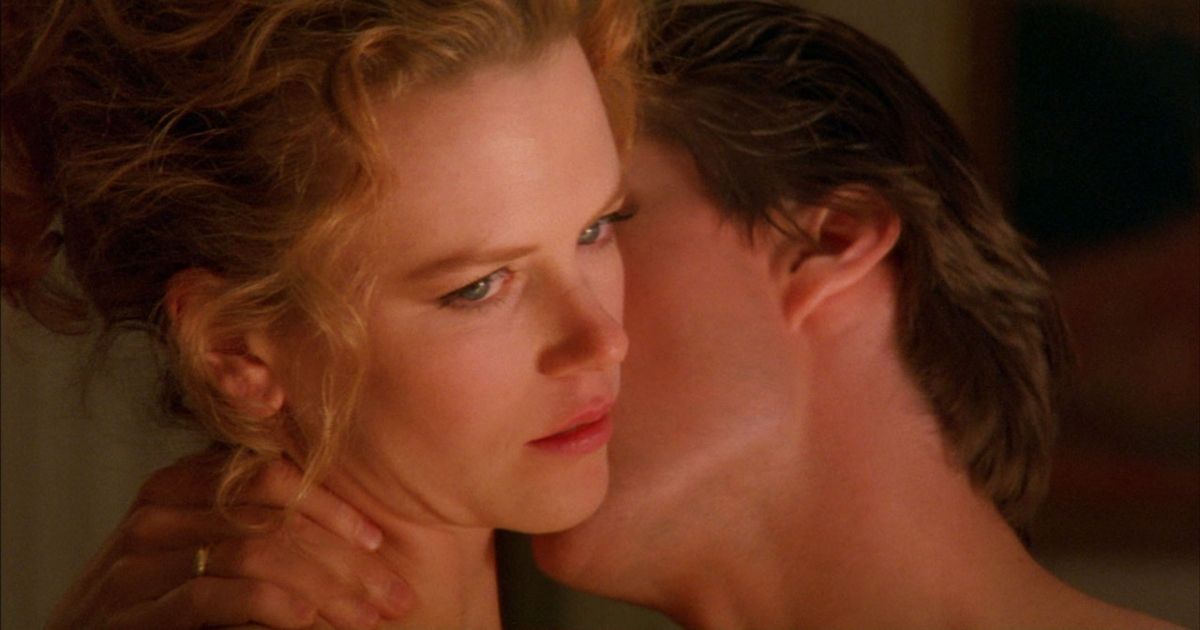

Not really as erotic as people thought it would be, and much more depressing, Eyes Wide Shut was met with mixed reviews upon its initial release in 1999. More about sexual repression than expression, audiences and critics were clearly expecting a different kind of steamy collaboration between Hollywood's "it couple", Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman. The movie took quite a while to make its money back, and the appreciation of its cultural value has been a slow burn as well. What was once considered to be somewhat of a disappointment is now seen as a fascinating relic: A time capsule of both Cruise and Kidman in full movie star mode, the end of Stanley Kubrick’s contribution to cinema, and a potent snapshot of American sexual politics in the late '90s. Almost a Christmas movie, almost a cultish thriller, this dream-like voyage subverts expectations at every corner, blanketing the charisma of both the film’s stars with detachment and isolation.

Cruise plays Dr. Bill Hartford, a wealthy Manhattan lawyer. Kidman assumes the role of Alice Hartford, a former art gallery owner who now stays at home to take care of the couple’s daughter. Bill’s friend Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack) hosts a swanky holiday party, and as the couple attends the function, the audience is immediately clued into the underlying tension between Bill and Alice. Almost immediately, Bill is whisked away by two young models with obvious carnal intentions. Left alone, Alice is swept up in the arms of a Hungarian gentleman who also makes his sexual desires painfully obvious. Bill notices that the piano player is an old college friend by the name of Nick Nightingale (Todd Field). Nightingale only has a moment to chat, but he urges Bill to come meet him at a jazz club on the Lower East Side if he finds some time. Any remaining holiday cheer plummets when Bill gets called up to Victor’s room to help resuscitate a nude model named Mandy (Julienne Davis), who’s just nearly overdosed on drugs. Bill and Alice go home with their marital fidelity intact for now, but the seeds of disarray have been planted.

The Kubrick Method

Beginning in 1996, the production of the film took a record 15 months to complete. Cruise and Kidman had initially signed on to a 6-month shoot, but soon realized the film would take far longer. Kubrick’s tendency to shoot an average of 50 takes per scene was the main culprit, causing problems with actors left and right. The Victor role was originally portrayed by legendary actor Harvey Keitel, but he quit the production midway through, claiming that he felt disrespected by the grueling shoot days. Kubrick wasn’t just killing time – his shooting method was a time-tested approach aimed at getting perfect takes out of his actors. He felt that once the scene had been beaten into an actor’s brain over and over, they’d forget their training and start to give a more authentic performance, or at least that they’d begin to embody the character on a deeper level.

Throughout the filming process, Kidman and Cruise lived together in London with their children. The ordeal was undoubtedly grueling – even causing Cruise to develop an ulcer at one point – but the actors have always spoken kindly of this time. Cruise has always insisted that Kubrick was never indulgent or unfair, just obsessively committed to the craft. In a 2020 interview with the New York Times, Kidman said: “[We] were happily married through that. We would go go-kart racing after those scenes. We’d rent out a place and go racing at three in the morning. I don’t know what else to say. Maybe I don’t have the ability to look back and dissect it. Or I’m not willing to.”

But considering the fact that the couple parted ways soon after, it’s hard not to wonder how the difficult film shoot may have affected their marriage. Playing jealous spouses on screen certainly couldn’t have helped, and the paparazzi at the time repeatedly used this unique production as fodder for Hollywood rumor-mongering. Tabloids at the time famously asserted that the couple were seeing a couples’ therapist during filming, leading Cruise and Kidman to file a high-profile lawsuit.

Dream Design and Subtle Symbolism

The other main difficulty of the film stemmed from Kubrick’s fear of flying. The aging director essentially refused to film outside of London by this point in his career, which of course created difficulties for a story set in Manhattan. To remedy the issue, Kubrick hired a designer to measure city streets on the Lower East Side, and then meticulously reconstruct a few blocks of New York City on a soundstage in London. This solution gives all of these external shots from the film a surreal, otherworldly quality. They look eerily familiar, but they’re almost too perfect in a sense, adding to the dream-like, fantastical reality. The interiors of the Hartford’s luxurious home were shot on a sound stage, allowing Kubrick’s cinematographer and gaffer complete control over the nighttime lighting scheme. They settled on a pairing of a warm tungsten hue emanating from the interior, and cold blue moonlight seeping in from outside. This iconic lighting design isn't just visually compelling; it adds to the dichotomy of the narrative. In this eerie world, the marital bed is warm, intimate, and safe, while the outside world is cold, blue, and dangerous.

Aside from this lighting scheme, the film also heavily relies on the light provided by strategically placed Christmas lights and trees. In nearly every shot of the film, Christmas lights are visible. This decision was partially a practical one, so that Kubrick could subtly enhance the source lighting of each location instead of bringing in big studio lights. But the main impetus behind setting the film at Christmas – the original story was set during Mardi Gras – is now seen as a deliberate move to tie in the movie’s themes with those of Christmas. As a time of celebrating family and holding loved ones close, setting the film during Christmas feels like a deliberate point of contrast.

These Christmas lights are a constant reminder in that sense. Everywhere Bill goes, he’s reminded of his own Christmas tree at home, where his wife and child lay waiting. As the pagan symbol of fertility, the copious Christmas trees seen throughout the film serve as beacons, shining a glaring light on Bill’s dark intentions. They’re also shiny, hazy, and dream-like in a sense, adding to the pervading atmosphere. They may even represent, according to Lee Siegel of Harper’s Magazine, the kind of duality of sexual desire; how the annual tradition of decorating a rapidly-dying plant is both elegant and tragic at the same time.

Sexuality Without the Sex

As the story unfolds, Bill’s desire for sexual gratification becomes blinding. The night after the holiday party, Bill and Alice get stoned and stumble into a frank discussion of gender and sexuality. She wants to know why he had his arms around two models at the party, and he insists that he had no ulterior motives. She wonders how he feels when he views the naked bodies of his female patients. She can't help but feel jealous about his access to others' bodies. She pushes the issue, asking him if he ever worries about her desires. He reveals his sad ignorance to female sexuality, insisting that women are naturally inclined to monogamy.

His blatant ignorance leads her to show her hand: she reveals that when they went to Cape Cod a year prior, she had an obsessive fantasy about making love and running away with a random young naval officer she spotted at the bar. She swears, although it’s inexplicable, that she would’ve run off with that stranger. To say the least, this admission cuts to Bill’s core. He can’t stop fantasizing about this sex scene, envisioning a reenactment in his head over and over. Kidman appears completely nude in this fantasy, but the tone of these vignettes is anything but sexy: set in an imaginary bedroom front-lit by a ghastly floodlight, their bodies writhe and tear into each other in a nightmarish, almost violent vision. While this part of the shoot was notably invasive for Kidman, Kubrick did allegedly give her final cut on the scene. Any shots that proved to be too revealing by her standards were excised without argument.

The rest of the film pans out as an impotent odyssey as Bill attempts to take revenge on Alice for her fantasy. He visits the home of a deceased patient that night, giving condolences to the patient’s now-widow. She essentially throws herself at him, but he denies the advance. Walking the streets of Manhattan afterward, he’s approached by a sex worker, who insists he come upstairs with her. Awkward and neurotic, he’s unable to go through with this sexual act yet again. Next, he stumbles upon the jazz club where Nightingale said he’d be playing.

They grab a drink after his set, and Nick reveals he’ll be playing another gig at a secret mansion orgy. Bill insists he comes along, and the iconic sequence of the film plays out. While nude bodies are seen throughout these cryptic scenes, the act of sex is only obliquely shown. And before Bill can fulfill his desire, he’s found out and removed from the premises. The last chapter of the film shows Bill retracing his steps, his desire for sex uniting with a need to regain control of his own life after being shunned and prostrated. His pursuit proves unsuccessful in both senses.

An Impotent Exercise

The idea of a ritualistic sex orgy in which anonymous impossibly beautiful women are assigned to men, essentially stripped of their autonomy, is an exaggerated extension of Bill’s male fantasy. He aspires to be like his rich, elitist friend Ziegler; to wine, dine, and fornicate with the special people on the tip of society’s pyramid. But in the end, the film seems to suggest that it’s not even possible for an upper-middle class man like Bill Hartford to fake his way to the top. His desire for infidelity is foisted at every turn, rendering him completely impotent. In the end of the film, Bill returns home to Alice and finds that she’s discovered his mask and placed it on his pillow.

He breaks down and tells her everything. In the end of the film, Bill and Alice shop for Christmas presents with their daughter and have one final conversation. They seem to have reached some kind of middle ground in spite of everything. “Maybe we should be grateful we’ve survived all of our adventures. Whether they were real or only a dream.” He asks her if she’s sure, and she replies: “Only as sure as I am that the reality of one night....A lone night of a whole lifetime can ever be the whole truth.” To which he replies “And that no dream is ever just a dream.”

In that sense, the couple have finally come to terms with the reality of each other's secret desires. He’s come to understand a little bit of the nuance of her sexuality, and how women are just as compelled by the idea of extramarital affairs as men. They’ve finally gotten it out into the open, or at least begun the conversation. It’s an isolated tender moment in a film that’s otherwise cold, detached, and full of marital strife. What was marketed as Cruise's fantastic orgy-filled romp through Manhattan turns out to be a satirical come-back-down-to-earth journey for a pompous, entitled, rich white guy. He never actually gets to have any sexual exploits in the film; it’s just a string of teases and temptations.

Bill realizes he doesn't understand the nuances of his own wife's sexuality, let alone the kinky underworld of elitist secret sex parties. The last line of the film, however, brings the subtext forward. Alice caps off the film with an all-timer: “I do love you. And you know there is something very important we need to do as soon as possible.” Bill isn’t catching on just yet – he wants to know what it could be. “F*&%,” she says.