“Medusa, in effect, became the archetypal femme fatale: a conflation of femininity, erotic desire, violence, and death,” says Kiki Karoglou, associate curator in the Met’s Department of Greek and Roman Art and curator of Dangerous Beauty. She explains: “Beauty, like monstrosity, enthralls, and female beauty in particular was perceived — and, to a certain extent, is still perceived — to be both enchanting and dangerous, or even fatal.”

In cinema, the femme fatale archetype tightly occupied the niche of detective thrillers, but over time they left the confines of this framework and ventured far beyond them to appear as double-crossers like Qi’ra in Solo: A Star Wars Story, anti-heroines in comic book adaptations like Catwoman in The Batman, or even lead their own movies, like Atomic Blonde. Adapting to changes, seductresses with insidious intentions remain relevant and continue to excite viewers, becoming women spies, organizing elaborate heists, or even being fabulous but utterly psychotic serial killers.

The femmes fatales are triumphantly marching through different genres, popping up in the most unexpected places. Their ability to seduce always gave off something almost supernatural, and in the satirical horror film Jennifer's Body, Megan Fox took it beyond the metaphorical, playing a darkly comedic succubus who literally ate lustful boys. The sci-fi thriller Ex Machina is an interesting modern take on the trope as well, as here the femme fatale is actually an android with artificial intelligence. While the femme fatale’s quest for female emancipation is wonderful, it is not such a straightforward linear development from objectification to feminism. Could it be that the classic femme fatale is a bit more complex, a bit misunderstood?

From Vamp to Femme Fatale

At the beginning of the 20th century, instead of the term femme fatale people used ‘vamp’ to describe beautiful but dangerous young ladies, implying their sexual vampirism. The fragile balance of alluring and predatory was perfected by Theda Bara, her somber black eyes drawing men to mysterious darkness in the silent film A Fool There Was, which was based on Rudyard Kipling’s poem The Vampire. Bara’s performances as a man-eater became the hallmark of the diva and strengthened her reputation as the first Hollywood sex symbol, something which extended to France with Musidora and Louis Feuillade's Les Vampires.

Another prominent film of the period is Baby Face, which was unique in its frankness on the delicate topics of sex, seduction, and freethinking. This infamous picture “was certainly one of the top 10 films that caused the Production Code to be enforced”, said Mark. A. Vieira, author of an illustrated study Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood.

The Hays Code adoption was largely accelerated by the immoral adventures of the heroine of Baby Face, performed by the brilliant Barbara Stanwyck, who made censors blush. Her character got inspired by the ideas of Nietzsche in the retelling of some unlucky drunkard, and slept with everyone up to the top, destroying the lives of all the men who laid their eyes upon her. The bold Baby Face caused a real outbreak, being a simultaneously deranged sensual fantasy and a spine-chilling male horror — all of these confusing sentiments resulted in a real storm that happened in the next decade, making femme fatale a recognizable movie archetype.

Femme Fatale in Film Noir

The golden age of film noir came in the 40s with cynical and stylish crime dramas, of which femme fatale is an essential element. For the most part, women appeared in crime stories only to thwart hard-boiled detectives from their way, by being treacherous or a source of all troubles. Femmes fatales were rarely outright evil, though; they were depicted as gray characters, women with the possibility of redemption.

Redemption, however, meant conforming to traditional gender roles and submitting to the main character (a man). If they chose to double down on their selfish, dark desires, they were punished by the narrative, often with fatal consequences. Mary Astor in The Maltese Falcon had men wrapped around her pretty finger, but the seasoned private detective did not buy into her games and, despite her pleas, gave her up to the police. The heroine played by Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity incited her boyfriend to the perfect murder of her husband and then ‘got what she deserved.’ At that time, the femmes fatales were still dependent on the opposite sex, which they needed as a tool to carry out their will.

Film theorist Laura Mulvey introduced the term ‘the male gaze’ and the prevalent film theory on how femme fatales were born of misogyny and embody the patriarchal society's fear of the growing role of women. Femme fatales are there to entice the male characters and, to an extent, the male viewer. In the 40s, women started to be especially active in the public spheres of life (voting rights for women only happened in the 1920s, after all). The sinful enchantresses denied the idea of motherhood, undermined family foundations, and did not want to remain at home. Since the cinematic women at that time could not control men socially, politically, or economically, they seduced, lied, and manipulated them through emotions.

Is the Femme Fatale Exploitative or Feminist?

In contrast with the generally accepted film theory, though, there is a feminist interpretation of the femme fatale. Surveys showed that in the 40s, femmes fatales actually caused women to become more interested in films and go to the cinema. Women mostly ignored the tragic endings of their favorite movies to enjoy the female beauties as fashionable, self-assured individuals who could be cold, prudent, and hungry for money but at the same time mysterious, liberated, and confident in their sexuality. They had a sharp mind, strived for independence, and actively went towards their goal. Thus, they combined qualities that are both frightening and alluring. Such complexities made femmes fatales interesting and multifaceted characters.

Conceived as a chauvinist device, the femme fatale was reclaimed as a personification of the need for female liberation and the fears of male oppressors. Blaser and Blaser write: “Even when [film noir] depicts women as dangerous and worthy of destruction, [it] also shows that women are confined by the roles traditionally open to them — that their destructive struggle for independence is a response to the restrictions that men place on them."

The Femme Fatale and the Sensual Death of the Male Gaze

Michelle Mercure also offers an alternative to Mulvey’s reading of the femme fatale’s ‘performance for the spectator,’ arguing that it denies the pleasure of the ‘male gaze’:

This tension that the femme fatale causes neither ‘contests’ the patriarchal structure, nor attempts to ‘converse’ with it. Instead, it speaks from within the patriarchal structure, without letting it understand her meaning. Exposing this voice that has been neglected offers feminism a unique way of communicating.

She brings up the classic film Gilda as an example, specifically the titular character’s striptease scene. While on the surface it is objectification in its most literal sense, the male lead doesn’t receive any pleasure from it, and neither does the viewer. He feels confusion and frustration, and Gilda refuses to provide an explanation, showing that while the performance was for him, it is she who controls the narrative.

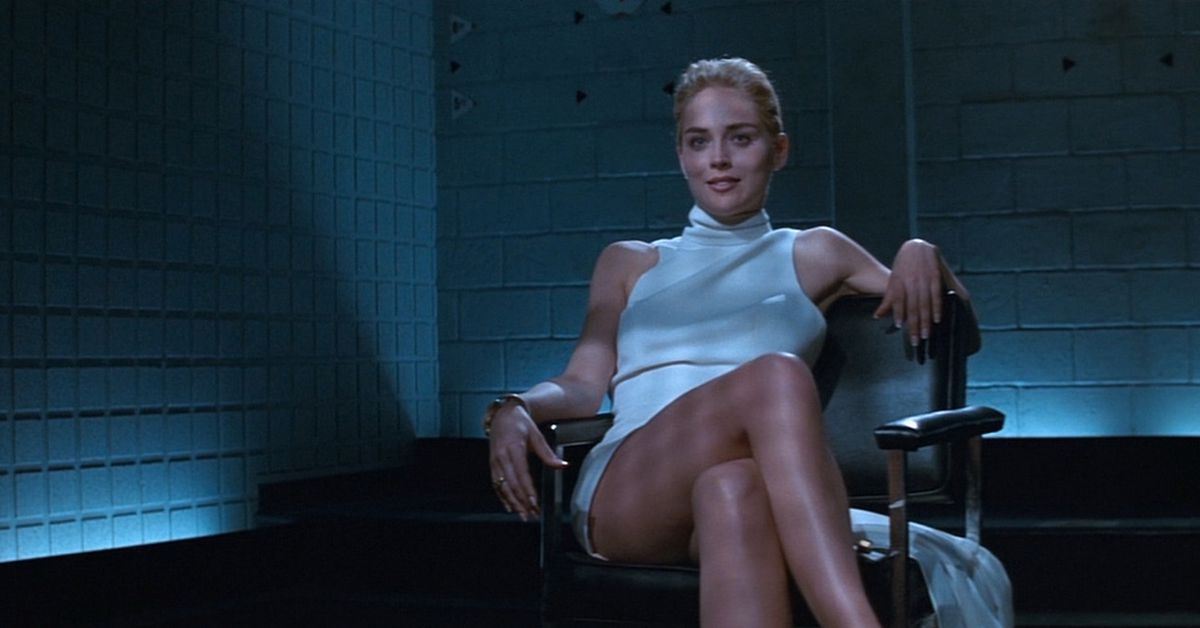

The presence of masochism and polysexuality might also put the femme fatale in a dominant role. While men depend on the other for sexual gratification, women are largely autoerotic, and hence need no one. Miranda Sherwin analyzes classic noir femmes fatales but also looks at the modern ones in Fatal Attraction, Body of Evidence, and Basic Instinct, noting that yes, the femme fatale is insane, violent, predatory, and, finally, dead. Nevertheless, she controls the film’s action until the end, the same way that women have haunted cinema since its inception.