This piece includes very minor spoilers for The Batman (2022).

Since Tim Burton's Batman in 1989, we've seen Gotham city re-imagined on-screen by a slew of different directors all with new, separate visions. Out went the 90-degree angles of Adam West and Burt Ward scaling buildings via grappling hook, and in came a rightfully gloomy and gothic approach that fit the character to a T. With the addition of Matt Reeve's The Batman, we have been introduced to a rain-soaked Gotham, dreary and grim. Its pavements drenched in as much crime as it is raindrops.

The 1989 screenplay to Batman by Sam Hamm and Warren Skaaren introduces the city as such:

The city of Tomorrow: stark angles, creeping shadows, dense, crowded, airless, a random tangle of steel and concrete, self-generating, almost subterranean in its aspect... as if hell had erupted through the sidewalks and kept on growing.

Batman and Batman Returns (1989-1992, Dir. Tim Burton)

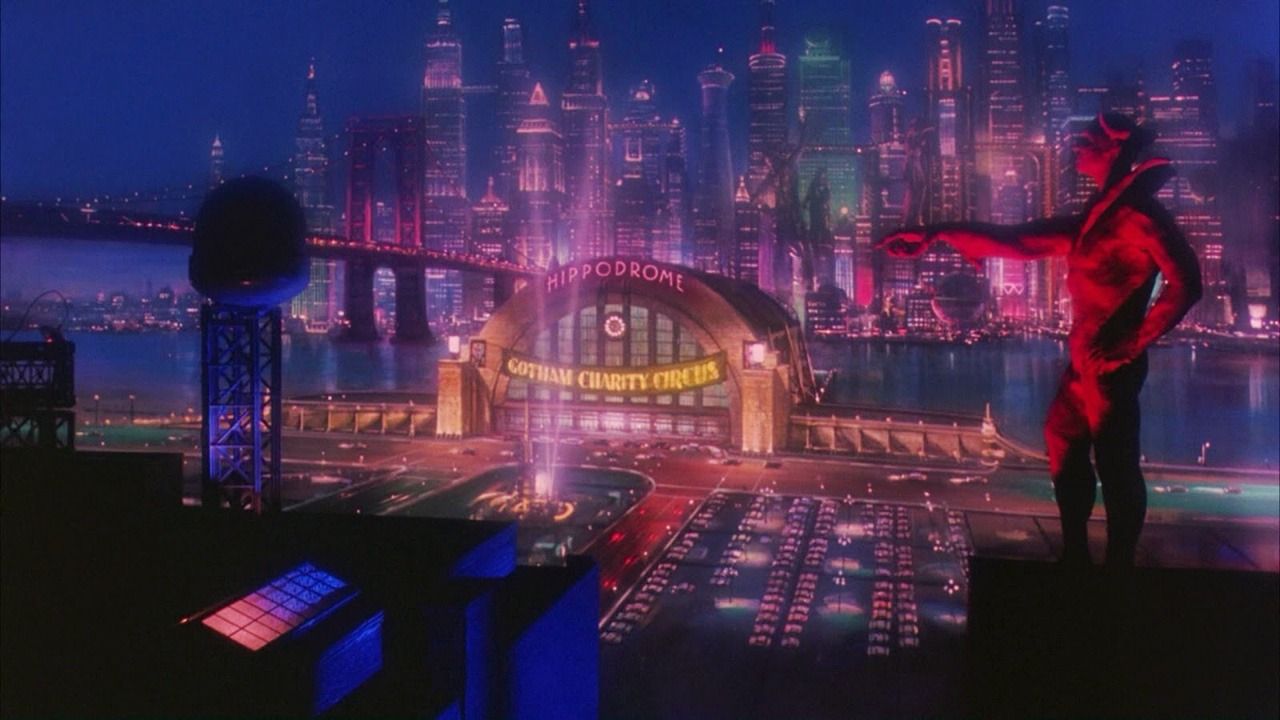

Over two films, Tim Burton's Gotham was allowed to be grimy. From the get-go of 89's Batman, we overlook a midnight city with high arching buildings. Smog and fumes bellow from vents. Chemical plants are conveniently placed nearby for villains to drop into vats. Aesthetically, Gothamites dress like they reside in the 1940s, with fedoras and long trenchcoats straight out of a noir, while the gangsters sport brash pinstripe suits.

Batman's establishing shot tells us that this is no mere New York or Chicago, but "GOTHAM CITY". Burton's Gotham immediately delights in its many alleyways for innocents to get lost in, and its hidden villains concealed like spiders waiting patiently in their webs. Over the (arguably too frequent) iterations of Batman on screen, alleyways have become something of a parody now, where someone is bound to be murdered, begging the question as to why any resident of Gotham would ever even risk it. But back then, they were almost part of the architecture, consumed beneath the high and suffocating DNA of the skyscrapers.

Set designer Anton Furst, with concept artist Nigel Phelps, created this Gotham at Pinewood Studios, devoting a whopping $2 million (in 1989) to their stand-in New York, and the result is a smattering of different designs. Physically, Gotham is made of steel and concrete, while featuring different varied colloquial designs like some unpleasant mashup (the church tower in Batman's finale, for example, closely resembles La Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, by Antonio Gaudí). Recognized critically for their efforts, Furst and Peter Young (set designer) would go on to win the Oscar in 1990 for Best Production Design.

As Burton had two movies to work with, he could expand on this groundwork further, plumbing the depths, leaning in to his eerie roots and adding a quite literal further level by revealing Gotham's (and Penguin's) lair in Batman Returns. Set during Christmastime in the city, the film makes Gotham look physically cold and uncomfortable with its position at this time of year, its buildings even more so impossibly high than before. When Batman, Catwoman, and Penguin overlook the citizens below, they gawk downwards like aptly grotesque gargoyles overlooking the normal life that they have been denied.

Batman Forever and Batman & Robin (1995-1997, Dir. Joel Schumacher)

As maligned as they are, Joel Schumacher's versions of Gotham present something wholly different to anything seen elsewhere. Comic in every sense of the word, this city is gargantuan and loud. Reflecting the director himself, this setting is big, elaborate, overbearing, and queer. Tower blocks are lit with neon, in garish reds and greens; muscular Adonis statues physically hold the surrounding buildings aloft, overwhelming them. These two depictions of Gotham City are consumer 1990s meets Greek sensibilities, all billboard advertising meshed with six-packs and togas. Schumacher's Gotham is a city that feels like it's done a line of cocaine, with a Viagra chaser.

These cities are the most interactive, as if they had been made out of Lego for a bored child to come along and kick to pieces (which may have inspired The Lego Batman movie). Take any of the chase sequences in these movies, and you'll see how much of the city's architecture is actually involved. In Batman and Robin, the Batmobile closes in on Mr Freeze (Arnold Schwarzenegger) and his henchmen's getaway vehicles. Thinking fast, Freeze creates a shortcut by way of the head of one of these statues and scales it from the shoulder down to the hand — successfully jumping the chasm by the statue's middle finger.

Long before Zack Snyder's heavy-handed Jesus allegories, Batman Forever and Batman and Robin's Gotham proposed a landscape which tells its citizens that gods live among us — and you have no choice in the matter.

The Dark Knight Trilogy (2005-2012, Dir. Christopher Nolan)

Christopher Nolan's Batman proposed a billionaire in a (mostly) realized world. Nolan's team asks If the crime-ridden Gotham was a real city, which would it be? Then answers loudly, "Hey! What about Chicago?"

As the only director with a trilogy of Bats to his name, Nolan could show a Gotham that evolves, devolves, and then repeats. By The Dark Knight, Nolan would utilize first-of-their-kind IMAX cameras to display his vision of the city. As a result, Gotham became a stretched landscape that was there to be blown up.

Like our eyes having to adjust to a new light, or a gritty version of The Wizard of Oz, The Dark Knight trilogy was a take on a character and genre we had never seen before. Scenes of quieter moments between men, and ethical ideas of right and wrong, were juxtaposed against intense action segments that filled the screen. With no black bars to stifle our view of this metropolis, it was a place ripe to be blown up and torn apart by any manner of psychopath mad enough to take it on.

Christian Bale's Bruce Wayne is also the best example of the ongoing series to really highlight the class differences in the city. Again bringing their own sensibilities to the table, London-born Nolan presents a class system at war with itself. Outside the super-elite trappings of Bruce Wayne's mansion (a location that can be burnt down and then rebuilt through inherited money, and shot in the very real Wollaton Hall in Nottingham), is a city with entirely Americanized structures and setups: straightforward, obtuse and by-the-numbers skyscrapers that tower over bums crouched over trashcans, and criminals preying on women at train stations.

Interestingly, as the weakest addition to the trilogy, The Dark Knight Rises has the most room to show off Gotham at its most desperate. Among a drastic turn of weather, whole football stadiums are reduced to rubble, and bridges are blown out. The citizens are reduced to slums and freezing to death under the rule of a dictator and his lackeys. As recognized by the slimy Phillip Stryver (Burn Gorman), Gotham presents a floating wasteland, and a walking-on-water moment (an escape, finally, from this horrible place) that could and will crack underfoot at any second.

The Batman (2022, Dir. Matt Reeves)

Echoing its tone and quasi-whodunit approach, Matt Reeve's Gotham is vile. It resembles the weather reports of Se7en and the Blade Runners before it. With its obnoxious and in-your-face advertising boards below skyscrapers with Victorian-style toppings, it is old meets new.

In such a brilliantly simple aesthetic choice, Gotham looks cold and uninviting, with almost constant rain. Shadowy doorways are specifically observed for far too long, making us believe that something (or someone) is on the other side. Gotham is shot so chilly and dank that if it isn't the dead of night and raining, then the sun is only about to go down so that the obligatory darkness may then resume.

Tube trains trundle along with gangs of thugs in cheap face paint taking in young and impressionable ne'er-do-wells. It feels like the people who live in this city were born here, but never left because their spirits had already been broken. Incel-turned-terrorist, Riddler, lives in a one-bed squat surrounded by obsessive newspaper clippings. On the opposite end of that, Gotham Manor is never properly revealed outside the far more prominent Batcave below.

In a kind of full-circle back to Burton, Reeve's Gotham City feels once again naturally grotesque: real and scrappy, but with comic book trappings. Unlike Nolan's city (which feels like a place his Batman was constantly adapting and reacting to), this Gotham feels like it's The Batman's home, and that he will shape its structure accordingly.