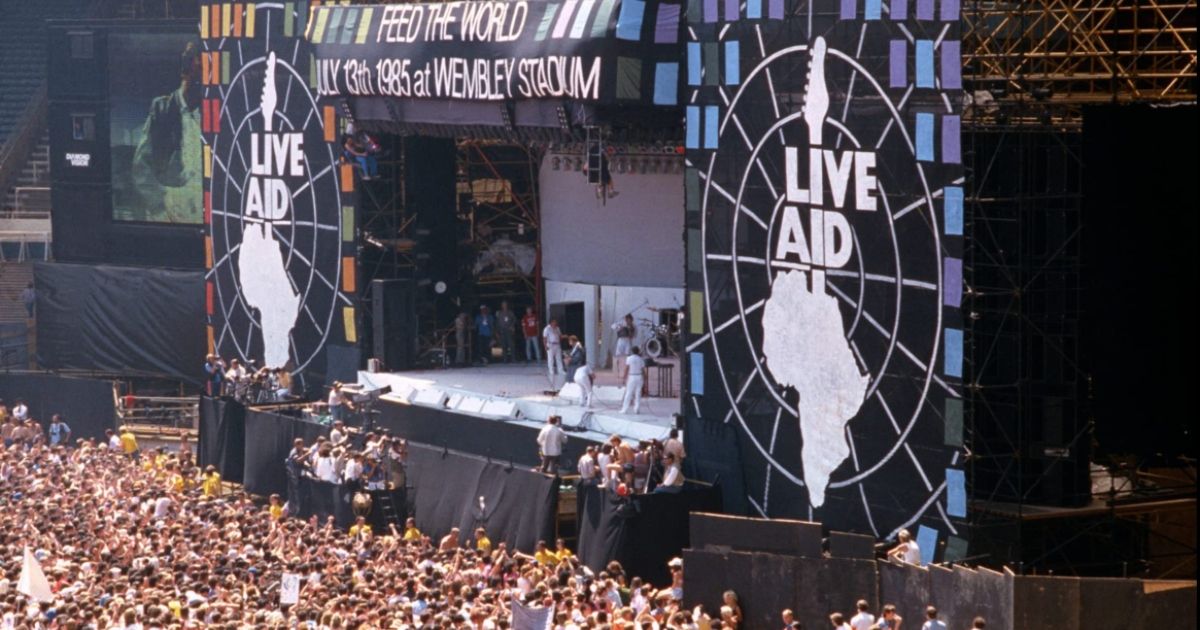

July 13, 1985 has gone down in the history books as a defining moment in music and pop culture. On that date, in two separate locations across the Atlantic — one in London’s Wembley Stadium and the other in John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia — punk rockers Midge Ure and Bob Geldof gifted the world a couple a dozen incredible performances for the ages.

But don’t fool yourself; this was still a live production, pulling together hundreds of singers and musicians in a hectic free-for-all. It could never live up to the magic in the movies. In the film Bohemian Rhapsody, the segment at Live Aid is presented as the first meeting of the band Queen in years, when in truth they had just released their 1984 album, The Works. Queen just concluded a supporting world tour and were in touring mode. The fact they were on the top of their game is a big “duh.” This is but one of the many shiny memories people have of the concert that doesn’t fit with reality.

In merry England, things went swimmingly, but for the Philadelphia venue the atmosphere was chaos, wrought with high tensions, monitors that broke (rendering musicians unable to harmonize with band mates in the middle of performances), and so many egos that it violated public safety rules.

Just like a movie, we just chose to remember the awe-inspiring moments and forget all the crazy, messy stuff. Despite our collective nostalgic memory, the rock gods were not smiling on the City of Brotherly Love that sweltering July day.

The Bum Note Heard Around the World

The hubris of staging two simultaneous concerts full of the greatest rock and pop acts of the last quarter-century eventually caught up with Ure and Geldof, especially the States-side concert of the two live broadcast shows. Live Aid deserves a feature film, sadly Bohemian Rhapsody ignored all the most insane details. While some bands and singers did enjoy the show and basked in the glory for the rest of their lives, it was probably a matter of sheer narcotics for most of the singers. Not surprisingly, a newly-sober David Bowie gave one of the sharpest performances.

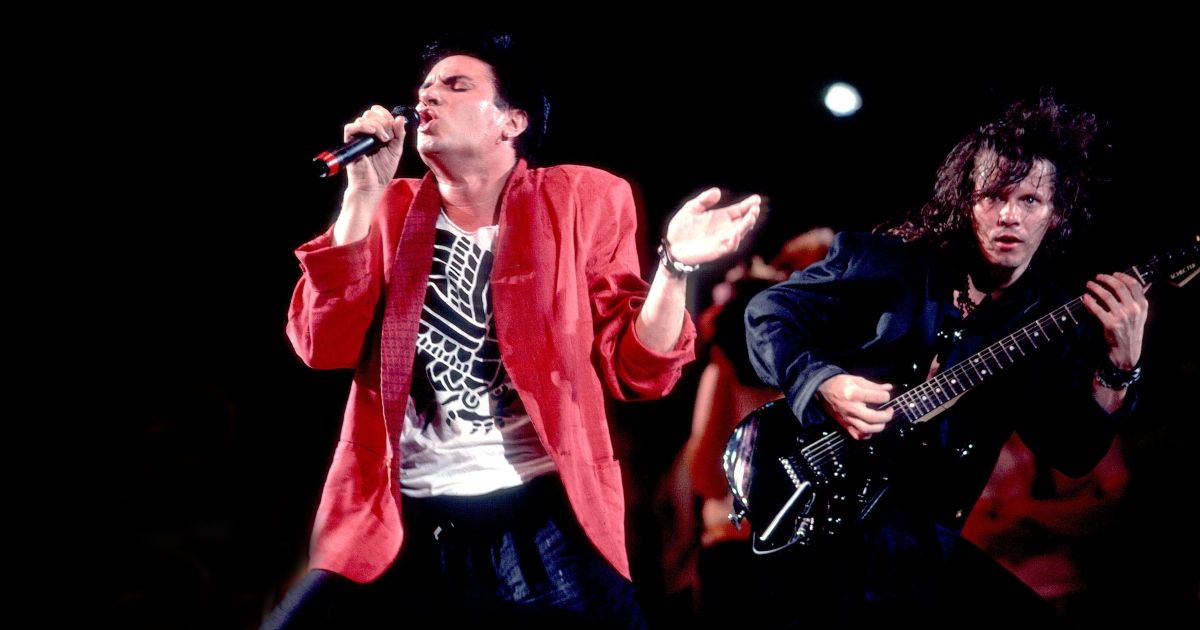

The stars didn’t so much align for Duran Duran as much as exploded in a supernova, getting yelled at by Stephen Stills for having the nerve to warm up before the biggest gig in their life. It went downhill from there. Their prime-time stint on the stage marked the end of the first part of their career. Lead singer Simon Le Bon famously missed a note (trigger warning for all you Duran Duran fans out there, it's a doozy) in the song “A View to a Kill,” the mistake punctuated with the squealing feedback that plagued the American show through the Pretenders and Judas Priest sets.

Years after, "the bum note heard around the world" still haunts him. To add insult to injury, the band was in such a poor state at the show they split up. After an impromptu goodbye after the bad set, the two factions split the band into two solo projects, the original lineup not reuniting for two decades, an unceremonious end to a landmark band. Bassist John Taylor sums up the sub-par show thusly (via The Guardian): "Andy and I had grown our hair and were doing the US rocker thing. They were doing the esoteric European artistic thing. It was all in the haircuts.The writing was on the wall."

This was a recurring theme. Due to gear that got fried in the heat, overworked technicians, or musicians arbitrarily picking obscure songs their newly minted bandmates never had time to learn or rehearse, Duran Duran was far from the only ones playing out of tune.

The Philadelphia Kamikaze Show

The feedback at this televised show was so bad that it hampered what was a one-in-a-lifetime show for Judas Priest to secure mainstream acceptance for maligned heavy metal artists. Rob Halford slayed the early part of his rendition of “Living After Midnight” only for his stellar falsetto to come to an ear-splitting crescendo as the audio system gained sentience and tried to sing along with him in a duet.

Madonna largely escaped the technical gremlins, but poor Phil Collins truly experienced hell. Already jet-lagged from flying on the Concorde in order to play at both venues, he felt out of place playing, and struggled to focus in the heat. "You could sense I wasn't welcome… Robert [Plant] wasn't match-fit with his voice and Jimmy was out of it, dribbling. It wasn't my fault it was crap." In retrospect, nobody remembers it fondly, the ad-hoc band barely having enough time to rehearse. Equipment broke down around them, nobody backstage bothering to tune guitars, the situation compounded by the fact the band had not played together for years. “My main memories, really, were of total panic,” Jimmy Page dismissed the show in ‘88 (via Rolling Stone), reducing it to a “kamikaze stunt.”

Collins’ own set went slightly better, but barely so. “I'm so sweaty that my finger slips off the piano key on ’Against all Odds,’” he recalled in his autobiography. You can see the embarrassment on his face. Then Sting had him sit in during his set, changing songs on the fly. "I'm singing the correct words, but the flash sod is ... improvising in his underpants. Meanwhile, the viewing million are howling, "Shut up, Collins! You're singing the wrong f**cking words!” Hilariously, Collins also described his Philly fiasco as “the bum note heard around the world,” earning his reputation as the most blunt man in showbiz.

Where Exactly Did the Money Go?

Musicians are not renown for their financial acumen, which is why what followed makes more sense in retrospect. Yes, the Ure-Geldof-helmed project raked in cash, but that’s only half of the equation. One big question that many people, either in the public or private sphere failed to ponder was where would all these hundreds of millions of charity proceeds actually go. A 1986 Spin magazine article revealed that much of the proceeds somehow went into the hands of warlords, who used a chunk of that $245 million to buy weapons. The full reality of the famine and humanitarian crisis is still being sorted out decades later.

That gigantic downer aside, even the bad performances are still interesting, as we witnessed our music idols pushed to their limits, looking like regular humans for once, sweating, struggling, and adapting to the ordeal. Crowds were rabid but forgiving of the myriad blunders and technical snafus, which is typical for outdoor venues. A large portion of those crowds were denied access to a good spot, forced to watch the show on a giant jumbo-tron. Still fans will recall it like they were in the front row, though the front row was arguably the worst place imaginable. The one moment that we really should remember in the whole affair was Bono trying to save a fan from the stadium’s crush after accidentally whipping the crowd into a craze. In comparison, Freddie and the boys’ set was boringly routine.