You may have recently gone into Jordan Peele's newly released film thinking you knew what to expect, and even if you were to be surprised, you knew you'd be ready for another Get Out-style thrill ride regardless. Nope. There's a strong chance you either didn't like Nope, or you liked it a lot and don't entirely know why — you love some ideas but just know that the pieces don't all seem to fit together. Well, there are several ways to interpret this love-it-or-hate-it film, some of which may even transform that hate into love, or at least respect. Andrew Chow and Laura Zornosa recently did a good job at explicating multiple meanings of the film for Time, for example.

Perhaps the most interesting (or at least provocative) way to interpret the film, however, is to view it as inherently about filmmaking itself; not just that, but about Jordan Peele's filmmaking, audience expectations, and the unhealthy relationship between fans, art, tragedy, and money. To do this, Peele creates an all-out spectacle that's deeply allegorical and exceedingly frustrating, frequently preventing any easy satisfaction. It's almost a prank, a big, visually splendid, richly thematic, wonderfully acted prank.

Explaining the Spectacle of Nope

After all, the filmmaker does warn you at the very beginning of the film with a quote from the minor prophet Nahum in the Tanakh: "I will pelt you with filth, I will treat you with contempt and make you a spectacle." There are, of course two ways to view this quote in relation to Nope — this is Peele talking to his audience, or this is Peele's audience talking to him.

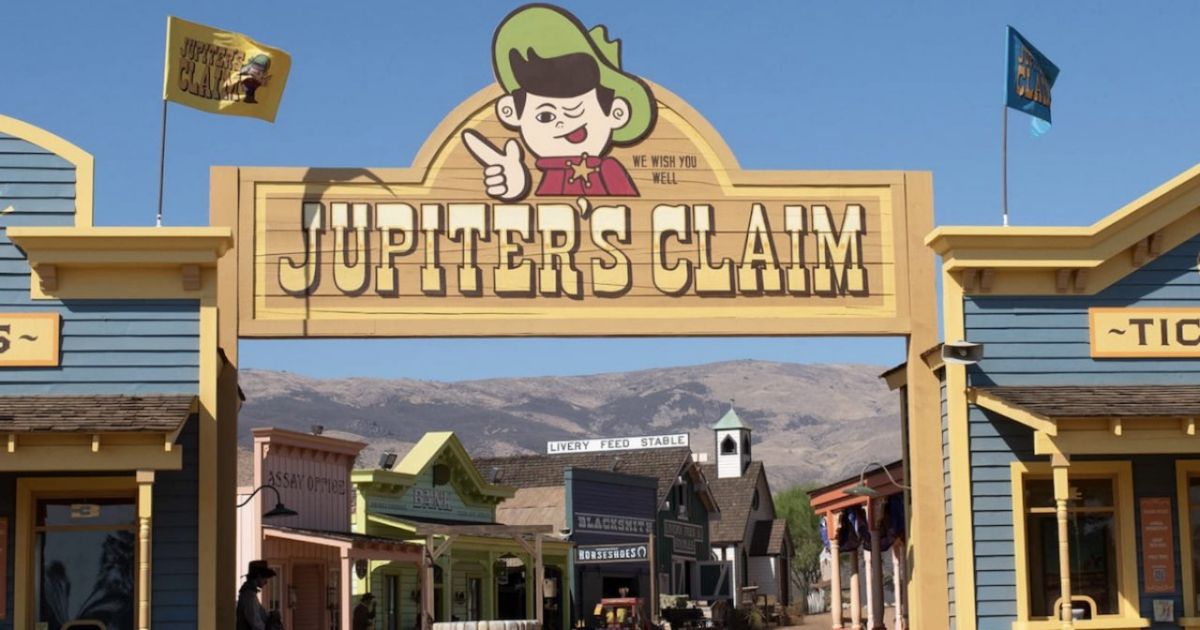

Though Peele purposefully convolutes the narrative, the story of Nope is actually quite simple. OJ and Emerald Haywood (the absolutely perfect Daniel Kaluuya and Keke Palmer, respectively) are siblings and owners of the Haywood Hollywood horse ranch after their father died from falling debris six months prior. They're struggling financially, having to sell some of the horses they've trained and wrangled to Ricky "Jupe" Park, a former child star who now runs a quasi-amusement park and rodeo. When Jupe was young, he starred in a sitcom with a chimp who went berserk one day and attacked the cast in a bloody, horrifying rampage. Jupe has memorabilia from his childhood sitcom days, charging people a fee to check them out.

OJ and Emerald (and, unbeknownst to them, Jupe) discover an alien creature camouflaged as a cloud; it's a kind of shapeshifting animal that usually takes the form of a circular saucer (the archetypal UFO) with a dark hole in the middle, a mouth that can suck up people and animals for food. The three of them see the alien less like a threat which must be stopped and more like a financial opportunity, if only they could get proof. Jupe attempts to turn it into an attraction at his park; the Haywood siblings, helped by broken-hearted electronics expert Angel and cinematographer Antlers, deck their ranch out with cameras and prepare a photo shoot for the alien monstrosity, if they can survive it.

Monetizing Tragedy Into Spectacle in Nope

With the plot laid out in this way, we can see a major theme arise — the commodification of tragedy, the profitability of using art as a way to capture the horrors of life. Profit and its relationship with tragedy is such an integral part of the film that the falling object which kills the Haywoods' father is a coin (regurgitated from the alien high in the sky). This is something Peele has become famous for, designing spectacles like Get Out and Us (and to a lesser extent Peele's reboot of The Twilight Zone) that use the art of filmmaking to create social commentaries that shine a light on homelessness, income inequality, white privilege, racism, and conformity. Viewers love it.

Jupe uses the tragedy of his childhood for financial profit, and now sees the murderous and horrifying alien as a profitable scheme, regularly sacrificing horses to it. OJ and Emerald see the same thing, and their family has a somewhat similar history of turning something awful into lucrative commercial art — they are descendants of the first person to appear in a motion picture, a Black man riding a horse in Eadweard Muybridge's Horse in Motion from 1878. Their opening spiel, given by them and their father before them (and presumably each preceding ancestor) on film sets where they're hired as wranglers, references the tragedy that this Black man never got the recognition he deserved, but that the wrongs can be corrected through the horse wrangling business of his ancestors.

Tragedy so easily becomes spectacle (something politicians know too well). The choice to name Kaluuya's character OJ is fascinating, and OJ Simpson is even referenced early in the film as a blond white woman tenses up with the mention of his name. OJ Simpson's more-than-possible murder of Nicole Brown became a massive cultural spectacle, one which included an epic car chase and a lurid courtroom drama watched by millions, along with, of course, many book deals and successful miniseries and documentaries. Simpson even had the audacity to write a profitable book titled If I Did It (with the word If almost invisible, hidden inside the letter I) after he was acquitted.

So what does this all have to do with filmmaking and fans?

Nope is About Aliens, and the Aliens Are Us

The very first shot of Nope is of an empty section of a studio audience, rows of chairs beneath flashing 'Applause' signs, and the seated viewer watches the empty seats of past viewers on the screen. From there, the references to filmmaking and audience members are relentless. Four main characters are or were all in the film business in some capacity; the only other main character, Angel, installs countless cameras and watches the footage from screens.

When four of them unite to film the alien, they essentially replicate a movie production, setting up cameras, communicating with walkie talkies, watching the video display, and waiting for the talent. OJ even wears a hoodie with the word 'Crew' on the back (from his time working on Scorpion King, of all things). This is a film crew, and they're making a movie; the alien is the subject, but maybe the alien is us.

Angel refers to the alien creature (or a certain kind of alien species) as 'The Viewer' and 'Viewers;' it hovers above them, looking down with what looks like an eye but is really a gaping mouth, consuming everything in its path. OJ tries to control it, to wrangle it the way he wrangles horses and to tame the beast; like the chimp, though, "some animals ain't fit to be trained," as one character says.

With fans ruining franchises through Twitter campaigns and barrages of social media hatred and outrage, and movies being more divisive than ever before, it makes sense that studios and filmmakers would want to tame the fans; they fear them but at the same time make a huge profit from them, just as the characters in Nope both fear and profit off of the alien. Is this alien us, The Viewers, the fans, the Netflix bingers and content consumers, devouring art like it's candy, turning all media into empty calories? Is our appetite incapable of being tamed? (There's of course arguments to be had of all sorts regarding what the alien represents; it could be tragedy itself, something awful that everyone's looking to monetize, or it could just be an alien).

The Viewer and Their Relation to Peele and Nope

The only thing which seems to throw off The Viewer is when a character refuses to look at it; The Viewer gets confused or passes over OJ or Emerald when they're steadfastly staring elsewhere. The Haywoods can make their film (and survive) only if they stop looking at The Viewer, and Peele can make his film only if he stops looking to the fans and the ridiculous amount of expectations they've heaped upon him.

Some have called him the greatest horror director of all time, a flattering but idiotic assertion after just three films (something even he finds preposterous), and his script for Get Out was named by the Writers Guild of America as 'the greatest script of the 21st century' barely a fifth of the way into it. That's a lot of pressure, and the way Peele survives is by looking away from it. He looks so far away from it in Nope that he seems to purposefully alienate the audience.

The audience is frequently tricked and frustrated throughout Nope, and one can almost hear Peele cackling in the backdrop. From purposefully dumb little jump scares of rubber-masked aliens to random cuts-to-black at crucial moments, Nope is filled with teasing to create cinematic blue balls.

Peele is constantly thwarting expectations and going against what the fan wants in Nope — he places Kaluuya, the charming star of Get Out, in a frequently silent role; his 'monster' is essentially a flying saucer (which inexplicably becomes a baroque display of origami near the end); he provides extremely little actual horror despite the moniker of 'greatest horror director' being thrown at him; he ends the film in an incredibly silly allegorical way with the alien eating a giant balloon (hollow entertainment that's filled with hot air); he literally calls the film Nope, as if to taunt the viewer; and on and on.

Nope Just Might Be Most Horrifying to Jordan Peele

None of this is to say that Nope is a bad film (well, maybe all of it is to say that; it's always up to each individual). In fact, it might be Peele's most interesting movie yet, an endless conversation piece that can be picked apart for days on end, and a massive, gorgeous spectacle that's a lot of fun if you let go of any preconceptions and expectations and simply trust Jordan Peele. In fact, when a character in Nope mentions The Viewer and says, "I think they trust me. If they didn't, I don't think I'd be here right now," they could practically be a stand-in for Peele discussing his audience.

Perhaps Nope is most horrific to Peele himself. This movie about making a movie almost seems like a manifestation of his fears as a filmmaker — like the chimp and the alien, will the viewers tear him to shreds? Can he tame and wrangle them, or does he simply have to look away to survive? Does he feel compelled to create a massive spectacle in order to placate and please the fans, to fend off their appetite for now? Nope often feels like Peele's response to the expectations and elevated anticipation that so many people had for his new film; whether the result is a playful, exquisitely crafted prank, a complicated metaphor about his own worries and the way fans can mediate between an artist and their work, or something altogether is up to each individual to decide.

In his landmark text The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord clarifies, "The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images." Maybe Nope isn't the spectacle, but rather the fans and their relationship to the filmmaker and the movies, their outrage and contempt, their insatiable consumption and endless demand. Maybe we're the spectacle.