Movies have been around now for more than a century. Over the years, they’ve evolved from simple, short reels of just a few seconds, to blockbusters lasting over three hours. Despite the difference in scale between the present day and the first movies, they have always inspired the same awe, joy, and passion in audiences. Being such an evocative medium, it’s no wonder that from the earliest days of its emergence as an art form movies have explored romance.

Love permeates almost every story we see, whether it’s a romance movie or not, because it’s next to impossible to depict humans without love being present. The shared experience of love and romance can create unity across cultures and time periods. Some of our most famous and beloved romance stories are from centuries ago, like Pride and Prejudice, which continues to be adapted again and again. But how did we get from the early, minute-long recordings of daily life to huge, star-studded, multi-million dollar romance productions? The industry has adapted and evolved so much since its inception, and this has affected the kinds of romance movies we see today. Let’s take a deep dive into the journey romance cinema has taken to become what it is in the present day.

The Silent Era: Novelty and Taboo

In the late-1800s and early-1900s, cinema was just getting started. The Lumière brothers invented the cinematograph, a device that allowed films to be projected for an audience, in 1895, which paved the way for cinema to become what it is today. Their film, The Arrival of a Train is the most well-known piece of work from this time period, which was a simple, one-minute shot of a train pulling into a station. Though, to us, this may not sound particularly exciting, its audiences at the time were shocked and thrilled. Writing for the Smithsonian magazine, Fritzi Kramer said, "films focused on social justice topics like race, poverty, crime, prostitution and birth control." Which shows that the silent era was certainly not as concerned with propriety and taboo as we might imagine.

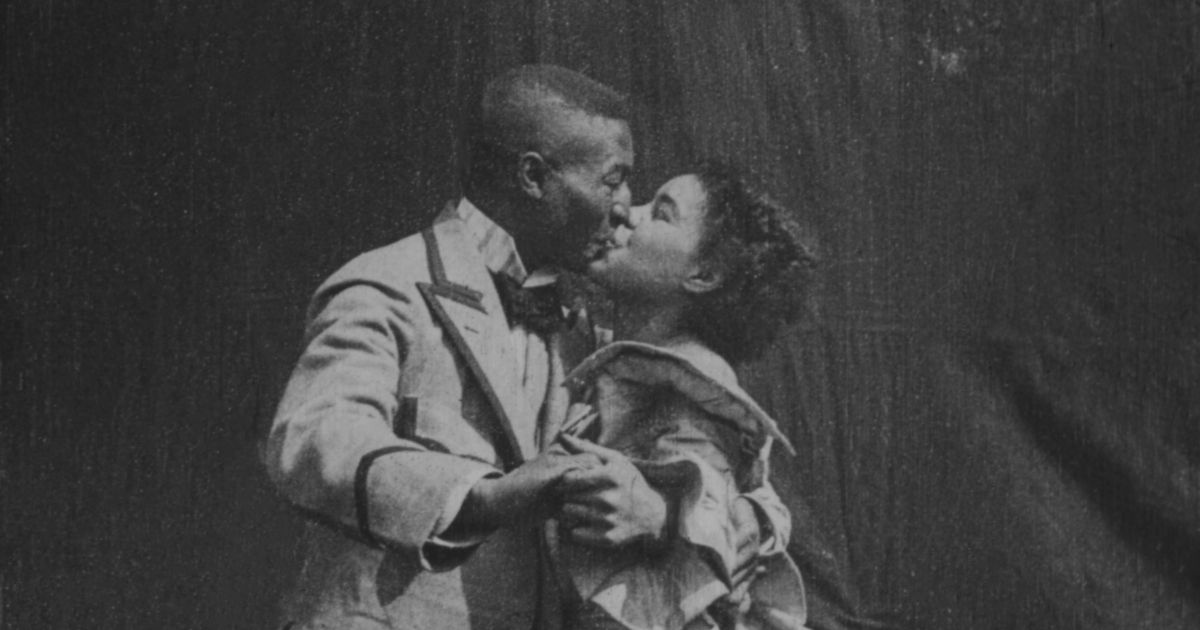

Thought to be the earliest depiction of romance on-screen, The May Irwin Kiss from 1896 was directed by William Heise and portrays a pair of lovers cuddling and kissing. In these early days, it was not yet cost-effective to produce and distribute feature-length films as the medium was so new. So, the film only lasts around 30 seconds, but manages to portray clear and charming chemistry. A couple of years later, in 1898, we have Something Good directed by William Nicholas Selig. This movie is similar to The May Irwin Kiss but instead, it’s the first portrayal of a Black couple kissing. The pair is so joyful that it’s impossible to watch without a smile on your face.

By the 20th Century, several feature-distribution alliances had formed that made it advantageous to produce feature-length films — those with multiple reels. This was because theaters could charge higher prices of admission for longer productions. It was at this point, in 1919, that Richard Oswald directed Different from the Others, a surprisingly early depiction of gay romance. The movie follows Conrad Veidt, a musician who is blackmailed for his sexuality and consequently outed. The relationship is portrayed tenderly and with care, and it’s a huge loss that almost every print of this movie was destroyed by the Nazis. There are a few reconstructions available online, but there are certain segments that may never be recovered.

It might be easy to assume that the representation of people of color and LGBTQ+ people in cinema is a relatively recent development. However, in reality, it has always been the instinct of filmmakers to depict love between non-white and non-heterosexual couples on-screen, as evidenced by these very early productions. The issue arises later when institutions took charge of the industry, controlling production power and imposing rules. But let it be known that marginalized people and their love have always been present in film.

Hollywood's Golden Era: Early Romantic Dramas, Comedies, and Musicals

Although it can be argued that Hollywood’s Golden Age began before the introduction of sound into cinema, it definitely didn’t get into full swing before the “talkies.” The first movie with sound to be released was The Jazz Singer in 1927. From then on, the ability to include speech allowed for a greater depth of storytelling in cinema. Some of the biggest movies from this era are Citizen Kane and the storied The Wizard of Oz, the latter of which also shows off the development of Technicolor. Another defining factor of this era is the Hays Code, introduced in 1934. This was a set of rules pertaining to what could not be portrayed on screen so as not to corrupt viewers' minds. These major components of the era obviously had a huge impact on shaping the romance movies of the time.

Some firsts for the romance genre in this era include Casablanca, the first romantic drama, Meet Me in St. Louis, the first romantic musical, and Trouble in Paradise, the first romantic comedy. It was an era of exploration and genre establishment. With the big studios such as MGM and Paramount up and running, there was a lot more money to throw around, which meant higher production value and a greater quantity of movies being made. This grand foray into new cinematic waters was, however, stunted by the Hays Code. The code included many rules, but, most importantly for romance movies, prohibited depictions of homosexuality and relationships between white and Black people.

Away from Hollywood and its code, in the 50s and 60s, the French New Wave was taking place. These movies intentionally rejected traditional filmmaking conventions and this led to some groundbreaking work. This includes Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour, a dark but beautiful exploration of love and memory. The central lovers-turned-friends are a French actress and a Japanese architect, who connect deeply despite their different circumstances. Hiroshima Mon Amour proves that there were steps taken forward during this time of censorship, even if it was in independent films outside Hollywood.

The Golden Age produced some timeless classics and was hugely important in forming the shape of genres we see today. But: think of what we could have had if filmmakers had been able to make uncensored films. Romance movies were set back to a more restrictive place than they had ever been since their inception by the code.

New Hollywood: The Rise of Independent Cinema and the Modern Rom-Com

By the 1970s, the golden age of Hollywood was over. The five major studios being deemed a monopoly and forced to restructure meant that costs were driven up as they no longer controlled every stage of production. This gave way to greater numbers of mid- to low-budget projects, which were often from independent studios. These lower-budget movies created space for more interesting and specific stories to be told as there wasn’t such high investment riding on their success. As a result, we got subtle and touching romantic dramas and quirky romantic comedies.

Romantic comedies take a more familiar shape in this era, and some of the most iconic and lasting rom-coms came from this time period. It gave us Pretty in Pink, When Harry Met Sally, You’ve Got Mail, and Notting Hill. One trend among this batch is the modernization of classic literature in the form of a rom-com, this includes the likes of 10 Things I Hate About You which is based on Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew and Clueless which is based on Jane Austen’s Emma.

In the world of romantic dramas, a noteworthy production house at this time was Merchant Ivory Productions. It was composed of producer Ismail Merchant and director James Ivory, who were partners in both romance and business. Together, they created movies such as A Room With a View and Maurice. Merchant Ivory movies were known for their equally beautiful scenery and romance. The fact that two gay men were in this position of respect and success and were able to produce a gay love story with Maurice shows a clear shift in attitude in the film industry.

Queer romances began to thrive in independent cinema with Desert Hearts, High Art, and But I’m a Cheerleader all being released between 1970 and 2000. My Beautiful Laundrette is a shining example of 80s independent cinema. It depicts a romance between Omar, a British-Pakistani man, and Johnny, who is white. The story balances heavy themes of racism and classism with lighter moments of romance, complete with bubble sound effects on the soundtrack. Each of these movies could not have been made prior to that point in time; independent cinema has been and will always be a haven for marginalized communities on screen.

The 2000s and 2010s: Continued Traditions, Anti-Romance, Queer Cinema

In more recent years, from the 2000s to the 2010s, three major trends in romance movies can be seen. One of these is the continuation of established traditions; the romantic comedy isn’t going anywhere. Another is a rise in romances with tragic endings or an emphasis on the idea that you don’t need romantic fulfillment to be happy. Lastly, queer romances have become more pervasive and representative of identities and cultures beyond cisgender whiteness.

Romance movies will always have a prominent position in cinema. Movies such as Pride & Prejudice, Bridget Jones’s Diary, and Easy A were all hugely successful and demonstrate the ever-present cultural appetite for romantic comedies and dramas. Additionally, there have been romances with supernatural or technology-based twists, showing that the genre will adapt itself to current tastes. The trend that followed Twilight is an example of how voracious these new takes can make viewers when timed correctly.

However, alongside these traditional romances, there has also been a significant rise in anti-romances. This concept is expressed in a variety of ways, it can look like a romance that may have a happy ending but with a cynical or violent twist, a plain old sad ending, or a focus on the romance of friendship over dating. These crop up in both comedies (Mr Right, Celeste and Jesse Forever) and dramas (La La Land, Lovesong). Interestingly, romances that incorporate technology are most prominent here with movies such as Her and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. This reflects a cultural wariness around how technology is impacting our romantic relationships.

Positioned between a continuation and a change is the state of LGBTQ+ cinema this side of the 2000s. It built off important groundwork laid from the ‘70s onwards, but has made enormous strides in terms of visibility and broader representation. From lesser-known projects like Tangerine, Pariah, and Rafiki to those that received Oscar nods such as Moonlight and A Fantastic Woman, queer and trans characters of color are reaching bigger audiences than ever before.

2020 and Onwards: What's to Come?

Looking forward, where might the romance movie go in the future? So far, we are seeing trends from earlier in the century continue. If we look at Ticket to Paradise, The Worst Person in the World, and Hulu's Fire Island, each of these suggests a continuation of the previously mentioned themes respectively. It seems unlikely that any of these movements will slow down any time soon, and it’s particularly hard to see a world in which there are no romantic comedies.

Moreover, with the current prevalence of streaming platforms, we might be experiencing a similar surge in rom-coms as the one that took place after the Golden Age of Hollywood. This is because these platforms are now funding a lot of original, mostly mid-budget, content. After stepping down from running WarnerMedia, Jason Kilar told Vox that he believes the state of streaming is a positive development for romance movies because "it’s a model that allows for more aggressive investment in romantic comedies and dramas." Hulu is a platform that's particularly involved in this situation, with Happiest Season, Crush, The Hating Game, and more under its belt all within the first few years of the 2020s.

Due to the fact that technology is only ever going to advance, and in turn, humanity’s preoccupation with it, we’ll definitely see more romances with that sort of twist. Speaking to the Los Angeles Daily News about his movie Her, Spike Jonze says technology is both "helping us connect and preventing us from connecting." For a genre that is so focused on connection and relationships, this makes technology highly relevant for romance movies. In a world destabilized by a pandemic and volatile politics, there's no telling what global event might cause a shift in culture next. But, if things continue as they are we'll be seeing more on this topic.

.jpg)