Love is hard. It would be hard enough to simply find someone you're compatible with, but that struggle is complicated by our preconceptions of an ideal romance: what we want our partner to look like, what their career should be, whether things are monogamous or "going somewhere" - sometimes potentially meaningful connections are severed because they don't square with our notions of love; other times doomed romance is pursued because it seems to embody what we want; and occasionally we do find mutual, unique love - but the relationship that carries it is complicated, messy, or plain destructive. Yet for all its difficulties, we cannot get enough romance.

Romantic comedies have been one of the most popular film sub-genres since the silent era, and for good reason: the formula is simultaneously grounded and fantastical, following normal quirky people struggling as much as we do before landing a cathartic fairy tale ending. These films are usually fun escapes; some of them are genuinely great; but they tend to reinforce ideas about love, happiness, and purpose that are unrealistic at best and destructive at worst.

In response to these troubling tendencies, a sub-sub-genre has developed: the anti-romantic comedy. These films follow the rom-com formula while challenging its conclusions, imbuing the meet-cute and happy ending with the pain, confusion, and sickness of real love (or what the movies have us calling "love"). Below we break down the five best anti-romantic comedies and what they have to say about love and connection.

5 A New Leaf (1971)

With her directorial debut, comedy legend Elaine May brought the ethos of the screwball comedy into the moral ambiguity of the seventies - and though studio interference dulled some of its bite (May ultimately disowned the theatrical cut), A New Leaf is still plenty dark and displays May's auteurist signatures: a skewering of the masculine ego; betrayal and selfishness in close relationships; and an unflinching, frequently claustrophobic gaze on its characters.

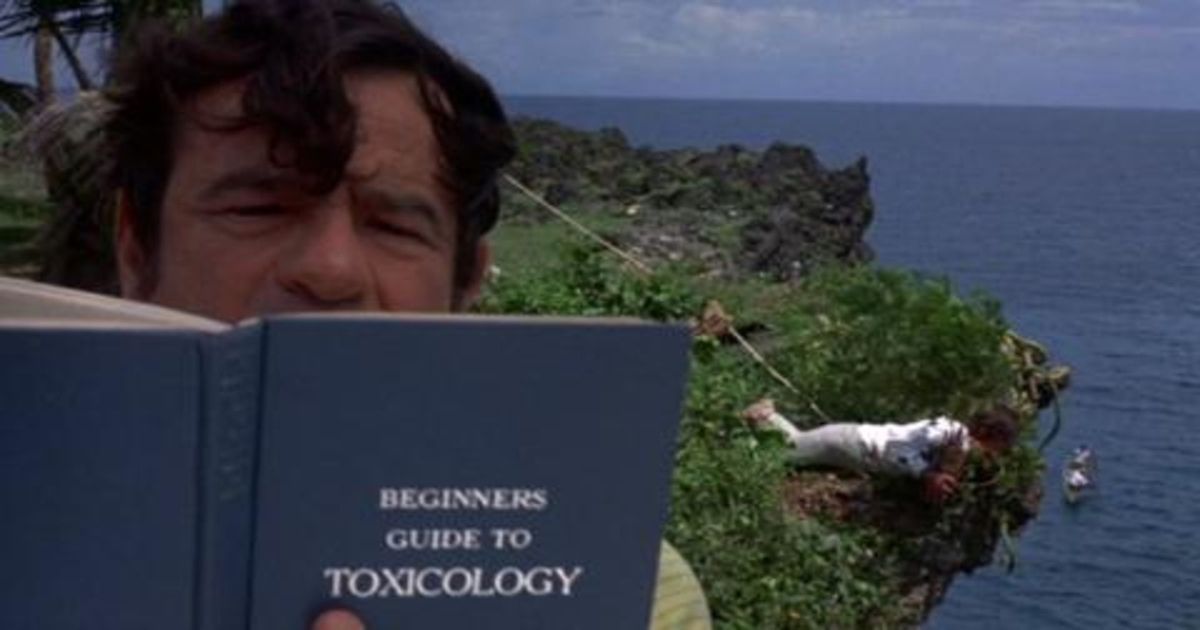

Walter Matthau stars as Henry Graham, an insufferable misogynist playboy who wants nothing more than to live his life as rich and uncaring - a raison d'etre that is challenged when his long-avoided accountant informs him that he has spent all his money. Henry decides the only course of action is to meet a rich woman, marry her, and murder her. He finds the ideal candidate in the bumbling botanist Henrietta (played by Elaine May, whose physical comedy is as stunning as her wit). Sweet, trusting, and clueless, despite her high IQ, Henrietta is the perfect candidate for Henry's scheme - and the film's tensions come from the audience's fear that he'll kill her before he realizes that he kind of sort of loves her (as much as he can love anyone). Henrietta's incompetence forces Henry to learn how to manage money, run an estate, and fend for himself; Henry's (duplicitous) attention gives Henrietta the confidence to make strides in her botany career. They're a perfect mismatch.

A New Leaf gleefully takes aim at the institution of marriage, the sociopathy of the rich, and the very idea of love. Henry is not capable of love - he is fixated on expensive stuff, and how that stuff reflects on his own importance. The opening moments feature a clever bait and switch: an electrical time sequence measurer comes across as the flat lining heart of a lover, and Henry appears to be a brave romantic that won't leave her side - until the camera pulls out, and we see that he's having his sports car checked by the mechanic, thus revealing Henry's true values. The car keeps breaking down because Henry is driving it improperly; yet he changes nothing in his behavior and seems to blame the car. This foreshadows his improper handling of wealth, which he learns to correct because of Henrietta; and while he never learns compassion (he only becomes conflicted about killing Henrietta when she gives her newly discovered plant species his name, bestowing her chance at immortality on him - in other words, reaffirming his sense of self-importance), by the end, he's at least figured out how to properly handle wealth, domestic life, and his metaphorical car - and Henrietta is the center of this change. That's the closest a man like Henry Graham can get to love, or redemption.

4 Sightseers (2012)

Love and romance ignite a part of us that craves importance. The feeling that you are someone else's entire world is enough to make your puny existence feel meaningful. So long as you and your partner(s) share that feeling, your lives and love are the most important things in the universe. There's another act people perform to give themselves an oversized sense of importance: murder. The power of one life snuffing out the other is a rationale cited by many serial killers to explain their murders. Ben Wheatley's Horror Comedy Sightseers asks what would happen if you combined these two forms of self-aggrandizement. The answer is disturbing, funny, and a little romantic.

Aspiring author Chris (co-writer Steve Oram) takes his girlfriend Tina (co-writer Alice Lowe) on a caravan trip. Tina is happy to get away from her mother/flatmate (who blames her for the death of a family dog), but she begins to have second thoughts about Chris when he "accidentally'" kills a man that littered and insulted him. Chris' assertion that Tina is his muse is enough to keep her around, but after another death, she confronts Chris, who confesses to the murders. Tina accepts this, and what ensues is a blood-drenched take on the road trip rom-com, featuring all the necessary detours and conflicts, plus a body count.

Chris' murder spree is closely tied to his writing ambitions. There is a hunger for profundity, glory, and importance - and Tina goes along with it, because she craves those things, too. Being the muse for murder is even more romantic than being the muse for prose; but ultimately we see that Tina's heart isn't in Chris or the murder spree. The romantic caravan trip was less about her boyfriend than escaping her mother via her boyfriend, and the murder spree was less about delusions of grandeur than the rush of killing. She's willing to follow Chris toward the abyss - but it isn't until the very end that we learn if she's willing to dive with him.

3 Modern Romance (1981)

Albert Brooks is best known as the fretful fish father in Finding Nemo (2003); the cold-blooded gangster in Drive (2011), and the free-loading father in This is 40 (2012) - which is a shame. While he's great in those films, his talents shine brightest in the slew of angst-ridden comedies he wrote and directed. A gem of his filmography is the acerbic pseudo-love story Modern Romance. Brooks stars as a nebbish B-film editor who breaks things off with his girlfriend, feeling their relationship is going nowhere - and immediately tries to get her back. Had the film stopped there, it wouldn't have been an outlier. Plenty of rom-coms follow lovers splitting and reuniting (e.g. the 1937 screwball classic The Awful Truth); but Brooks goes a step forward, bringing his couple back together at the midpoint, then splitting them apart, then bringing them together, and leaving us with a title card that implies the cycle will continue.

Modern Romance has an unabashed goofiness to it, but there's a darkness underneath. Brooks takes advantage of his schlubby likability to create a protagonist that is off-putting and morally murky without being unwatchable. The character is controlling, indecisive, and obsessive - no doubt this is why Stanley Kubrick was a fan of the film: he admired its portrayal of jealousy, a theme he later explored with Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

When the hapless editor isn't relying on romance to fix his discontent, he's trying exercise, Quaaludes, and the health food craze - all to no avail. His sisyphean efforts find a perfect metaphor in the B-picture he's editing, a dreadful film that he and the insecure director try to make great - but post-production cannot fix an awful script and lousy footage, just as romance cannot fill a hungry void.

2 Three Colors: White (1994)

The cinema of Polish master Krzysztof Kieslowski is populated by ideals and the people who try (and fail) to live up to them. His final opus was the Three Colors Trilogy, a series of loosely connected French films that each based their themes and color motifs on one of the ideals of the French Revolution: Blue (Liberty), White (Equality), and Red (Fraternity). Despite their relationship to modernist liberal ideology, none of the films approach their thematic questions in political terms - though White is the closest to overt economic commentary. It follows Karol, an impotent Polish man who is divorced by his beautiful French wife Dominique. Following the divorce, Dominique seizes his property and finances (through legal and illegal means), leaving the immigrant with nothing but a suitcase (he also manages to get a hold of a pearl-white bust of a woman, which he clings to for its symbolic significance). He is smuggled into the newly capitalist Poland in the suitcase; when he arrives he is beaten and the bust is broken. Karol then throws himself into the cut-throat culture of post-Communist Poland, eventually acquiring a great sum of money - all in a revenge scheme to frame and humiliate Dominique.

The film examines equality through inequality. An obvious example is Karol's lack of autonomy as a Polish-speaking man in France - his native wife is able to exploit and ruin him with no repercussions, because the court of law is designed to protect her, not him. Another example is post-Communist Poland. Capitalism may be intended as an even playing ground where anyone can make their own wealth (at least, according to its proponents), but its manifestation in Poland creates a sharper divide between the rich and poor; and while some are able to climb the system, it comes at the cost of others. Most importantly, the film explores inequality through a truly bizarre take on the favorite subject of screwball rom-coms: the battle of the sexes. The social inequality of women in a patriarchal society is subverted by giving all the power to Dominique. Karol's quest is driven by desire as much as revenge: he doesn't merely want to get even; he wants to prove himself to her. The way to do this is not by making them equal - it is by swapping the unequal balance in their relationship. It is a question of dominance.

All this humiliation and cruelty is motivated by a warped concept of love. This is symbolized by one of the most prominent white objects in the film, the bust. Karol clings onto it as he returns to Poland, where it is destroyed, symbolizing the loss of love and any sense of equality with Dominique. As he climbs the capitalist ladder, Karol fixates on the reconstruction of this bust: this is his way of getting Dominique back - and the twisted part is, it works. By the end Dominique has lost all freedom and autonomy, while Karol is completely unencumbered - and it is only at this moment that she asks to restore their marriage. This notion of love as conquest or the realization of an abstract ideal ensures that equality in relationships is impossible - and those of us who need the chase, the games, and the bold displays would have it no other way.

1 The Heartbreak Kid (1972)

If A New Leaf displayed Elaine May's sensibilities leashed by studio interference, The Heartbreak Kid shows her running free, sinking her razor-sharp teeth into unsuspecting (but much deserving) chauvinists, cheaters, and self-proclaimed chasers of the American Dream. The Neil Simon-penned screenplay begins with Lenny, a small sporting goods shop owner, courting Lila (played with devastating sincerity by May's daughter, Jeannie Berlin). Their romance plays out in a quick succession of telling shots: Lenny speeds around in his sports car, practices flirting in the mirror, tries it out on Lila, and almost goes all the way with her - almost, because she wants to wait until marriage. Once they are married (and consummated), Lenny finds everything Lila does grating, and it becomes clear that he didn't marry her because he loves her; he married her because he can't take "no" for an answer, and he'll do anything to turn a "no" into a "yes" (even if the "yes" is an "I do").

Lila gets a terrible sunburn on the first day of their honeymoon in Miami Beach, giving Lenny room to pursue Kelly, a rich witty college girl who represents everything he decides he wants.

Though it resembles a romantic comedy, The Heartbreak Kid is not about love. The only character genuinely in love with anyone is Lila, and she ends up sobbing and catatonic in a seafood restaurant (that break-up scene is one of the greatest in American history: it can simultaneously be read as dead serious/painful and completely hilarious). Every other character is motivated by a complex cocktail of desire and self-absorption. Kelly certainly likes Lenny, but he's mostly an amusing way to annoy her father, who hates him at first sight (it is clear that her father is bigoted, classist, and possibly antisemitic, though his loathing of Lenny proves justified). She isn't exactly thrilled when Lenny follows through on his promise to come to Minnesota, a harsh cold contrast to the warm fantasy of Florida. Kelly is only won over by the impression that her love for Lenny is remarkably grown up and sophisticated.

And then there's Lenny, one of the most fascinating characters in comedy history. Charles Grodin imbues him with a smarmy sense of self-awareness: with each lie and manipulation, he sees what a jerk he is - and seems to think that seeing it is enough to forgive his behavior, which is - after all - in the noble service of true love and happiness. Lenny comes to represent a bottomless pit of wanting, in love with nothing except the romance of the chase, the idea that nothing is out of reach if he wants it badly enough. The only problem is that once he gets it, he has no more purpose. He is not left with love; just a tremendous hole no grand courtship or achievement could ever fill.

.jpg)