As most stories in Hollywood go, the palatable version is rarely the honest one. In the film 21, the predominantly Asian-American MIT students are replaced with white characters and actors, given that even though the truth wasn’t white, the audience would be. It may be a surprise that the first Hollywood heartthrob — prior to even Rudolph Valentino — was a man named Kintarō “Sessue” Hayakawa. But it shouldn’t be a surprise that, like the women screenwriters who made Silent Hollywood, Hayakawa’s legacy has been, quite literally, torn down in the century since.

Hayakawa’s story begins with a dare: a young man in the Japanese naval academy diving to the bottom of a lagoon and rupturing his eardrum, his familial intent to become an officer breaking in tandem. An aristocratic family, Hayakawa attempted seppuku (stabbing himself 30 times), surviving and redirecting careers to appease his father: a banker with a degree from the University of Chicago (he even played quarterback there and was once given a penalty for taking down an opponent using jujitsu). Waiting in Los Angeles to board a ship back to Japan, Hayakawa worked a multitude of odd jobs: an ice cream scooper, a restaurant worker, a theater actor in Little Tokyo — the latter where he met Tsuru Aoki, a celebrated actress who found Hayakawa extraordinary. Aoki invited Thomas H. Ince, the biggest producer-director of the time and “Father of the Western,” to see just how brilliant Hayakawa was.

Hayakawa was the revelation that the late Marlon Brando embodied four decades later: “muga,” a naturalistic version of acting where he attempted to do as little as possible rather than behave theatrically like all other actors of the 1910s. A dumbstruck Ince was willing to do anything for Hayakawa to reprise the role onscreen for Ince’s new production company, but Hayakawa was desperate to get back to Japan and please his father, demanding a hilarious and impossible $500 a week from Ince for taking the role (about $14,000 a week in 2022 dollars). Knowing the future Hayakawa had, Ince actually accepted.

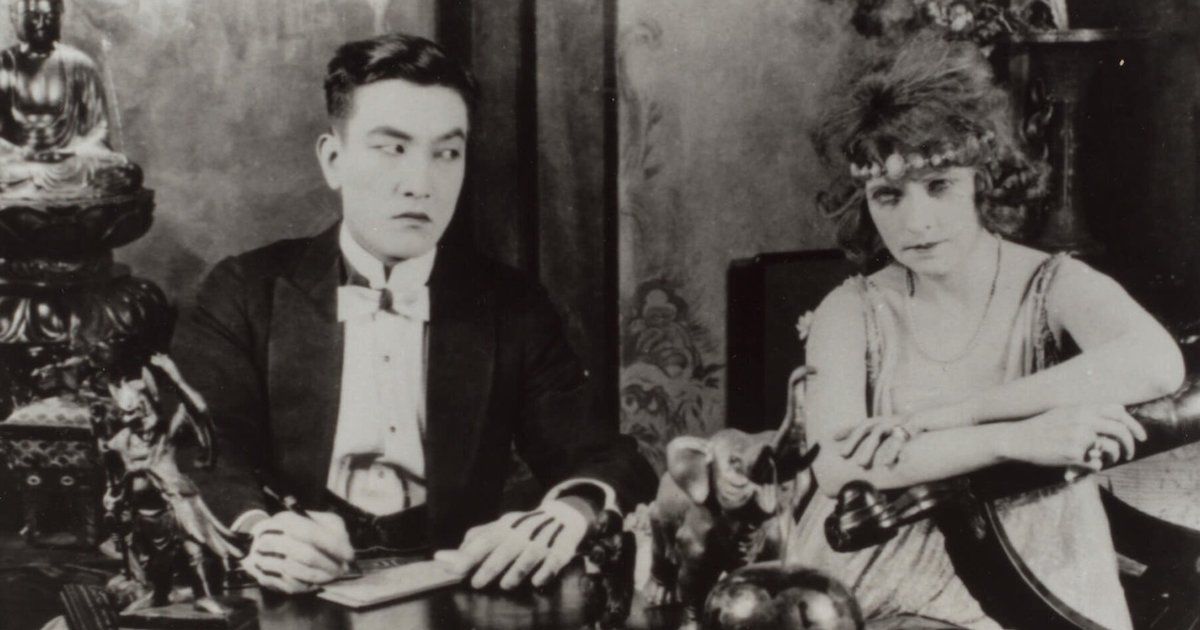

The Typhoon (1914) was a smashing success, resulting in a follow-up film with both Hayakawa and Aoki, The Wrath of the Gods (1914), the two having been just married in real life. Right after, the legendary Cecil B. DeMille sought Hayakawa for The Cheat (1915), making him an overnight star. While the best silent movies were still coming into their own as artistic expressions rather than scientific gimmicks, American white women had launched to the theaters in a sudden rush to see the beautiful Sessue Hayakawa on screen as the forbidden Japanese lover: a wealthy ivory merchant with which the female protagonist has a somewhat villainous affair. In Japan, there was little word of Hayakawa’s advancements, and it would be years before he told his father what he was still doing in America, as acting was seen as a loss of status.

Sessue Hayakawa Became Hollywood's Highest-Paid Actor

Outside Japan, Hayakawa became one of the most sought actors in the world given how women followed wherever he graced, becoming a regular handsome tempter or martial arts villain again and again through the 1910s and 1920s. He’d eventually asked for $7,500 per week for roles (about $117,000 weekly in 2022 dollars), making him the highest paid actor in Hollywood and even building himself a castle that became a city landmark. Purchasing a carload of liquor before Prohibition took effect, his castle was the most famous party destination in Hollywood — Hayakawa once losing nearly a million dollars gambling in a single night. In terms of fame and social status, he was considered equal to only Charlie Chaplin and John Barrymore.

However, Hayakawa was inundated with orientalist and anti-Japanese sentiments by both colleagues and the American public, a torture he himself attributed to the fact that he’d been portraying Japanese men as villains. Done with typecasting, he created the first Asian-owned production company in Hollywood, Haworth Pictures Corporation, where he’d make $2 million in just three years ($31 million today). After creating 23 movies better honoring Japanese men, Hayakawa abandoned Hollywood, likely due to vicious tabloid rumors of Aoki dying by suicide, or an alleged attempt on his life by the anti-Japanese Robertson-Cole Pictures Corporation.

Hayakawa found smashing success acting internationally, even performing in London for King George V and Queen Mary. In Russia and Germany, he was considered one of the finest actors to ever emerge from across the pond. But France was where his crown held the most weight, his performance in the silent film La Bataille (1923) alongside his wife Aoki making him one of the most famous young men in the country (especially among French women). He’d occasionally return to the U.S. to make pictures, but after 1930s legislation was introduced forbidding all displays of interracial romances in Hollywood, Hayakawa’s greatest financial asset as a romantic item for white woman was lost, and he stayed in France permanently.

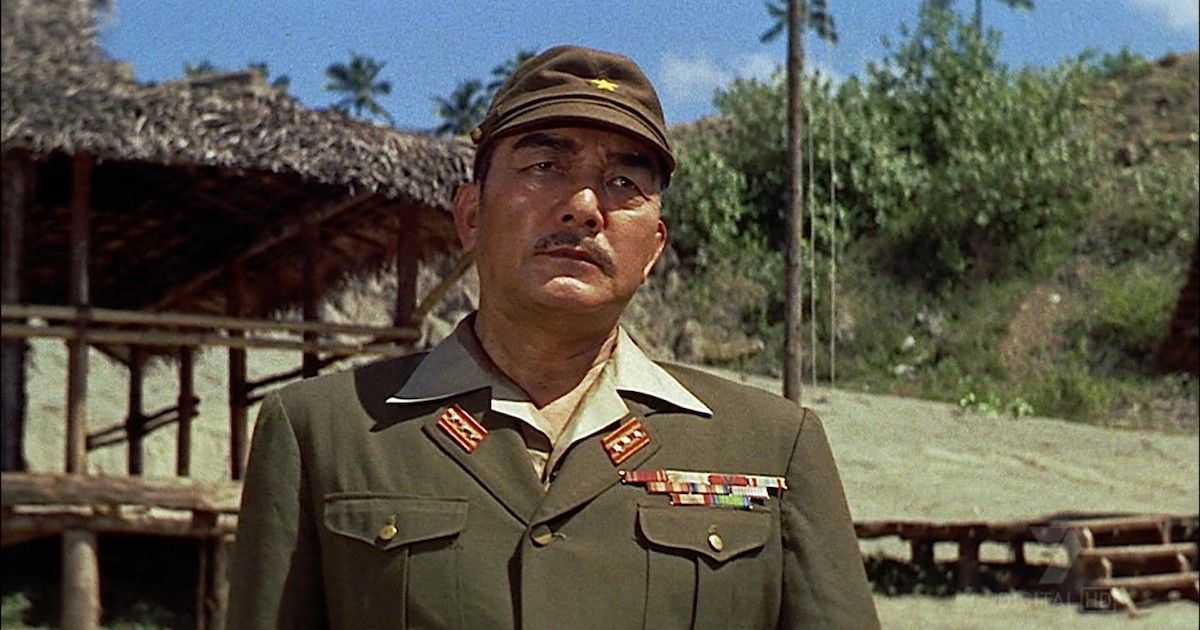

After filming Yoshiwara (1937) in Paris, a talkie that caused less enthusiasm for Hayakawa given his now noticeable accent, the Nazis invaded in 1940, trapping Hayakawa. He survived by selling watercolor paintings, aiding the French Resistance and Allied fliers before vanishing. It wasn’t until Humphrey Bogart uncovered the nomadic Hayakawa in 1949 and asked him to return to the U.S. for his film Tokyo Joe that the U.S. government interrogated Hayakawa to ensure that he didn’t in any way aid the Axis Powers — which he didn’t. Still, the anti-Japanese sentiments that persisted even after the war erased Hayakawa from pop culture history.

Hayakawa's Legacy Today

Hayakawa’s final major film was The Bridge On The River Kwai (1957), where he became the first man of East Asian descent to be nominated for an acting Oscar. He recognized it as the highlight of his career, devoting his remaining years to becoming an ordained Zen master and living peacefully. In 1973, he died in Tokyo of a cerebral thrombosis complicated by pneumonia.

Sessue Hayakawa’s legacy remains complicated, given that his biggest films, three of which are in the Library of Congress, largely portrayed East Asian men as villains. He’d won the desires of American and European women greater than any man before him, but much of it came from the orientalist promise of danger to which his roles catered. It’s hard to say if Hayakawa’s legacy has been disappeared by Japanese-sympathetic film historians given he was a “traitor” to the Japanese image or by anti-Japanese Hollywood tycoons given he was a Japanese producer who tried to later rehabilitate that image himself. In the end, Hayakawa’s antics and advancements may be the biggest Hollywood story that never gets told. Today, his castle has been long torn down, its buried debris shouldering a gas station.