Andrei Tarkovsky has an unmistakable, everlasting presence in contemporary cinema — from the first season of True Detective to Christopher Nolan’s blockbusters; in the smooth panoramas of Alejandro González Iñárritu, the associative montage of Terrence Malick, the elaborate staging of Tarsem, and Lars von Trier’s use of color; in how Nuri Bilge Ceylan portrays landscapes and elemental forces, in the unhurried rhythms of Carlos Reygadas, Krzysztof Kieslowski, Bi Gan, Hayao Miyazaki, and many other adherents of slow cinema. Tarkovsky’s influence is exorbitant (even extending into video games like S.T.A.L.K.E.R.), and his figure is intimidatingly immense to the masses: he has always been considered too elitist, obscure, and extremely difficult to understand.

Tarkovsky's greatly philosophical films are generally distinguished by that extreme simplicity beyond which all art ends, like the torn-off skin that bares the bundle of nerves. Greatly influenced by his poet-father, the Soviet director continued his poetic traditions albeit through a different medium. Seven years after the release of his movie Stalker, the tragedy of Chornobyl happened, and many surprisedly pointed out obvious coincidences, down to the details like the 4th bunker mentioned in the film corresponding to the 4th power unit of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant — foreseeing is not uncommon among poets, after all, and sometimes sci-fi predictions come true.

Far Out points to the popular sentiment that Stalker “is not only his magnum opus, but quite possibly one of the greatest films ever made, revealing the hypocrisy of our empty dialectics and our petulant arrogance through a simple allegorical tale.” Changed locations, reworkings, and complete reshoots, the mystery of Chornobyl and multiple deaths of the crew and the cast members, possibly contaminated by the chemical plant upstream from the filming set, as well as the subsequent banishment of Tarkovsky from the Soviet Union — all of this added to the power of Stalker, a film as hauntingly beautiful as it is unfathomable. Since it first appeared on-screen, Stalker has made a stunning impression, the meaning of which was clear to very few people.

The Making of Stalker

It is only fair that one of the greatest sci-fi movies of all time had one of the most difficult productions in filmmaking history. According to the original plan, most of the film was to be filmed on location in Central Asia, in Tajikistan, not far from old Chinese coal mines. Part of the film crew was already at the location, when a seven-point earthquake occurred, resulting in destruction and human casualties. A new location, chosen in a hurry, was an abandoned power plant on the Jagale River in Estonia, which dictated a completely different construction of mise-en-scene and new directorial decisions. The script, adapted from the novel Roadside Picnic, was becoming increasingly less fantastical and more symbolic.

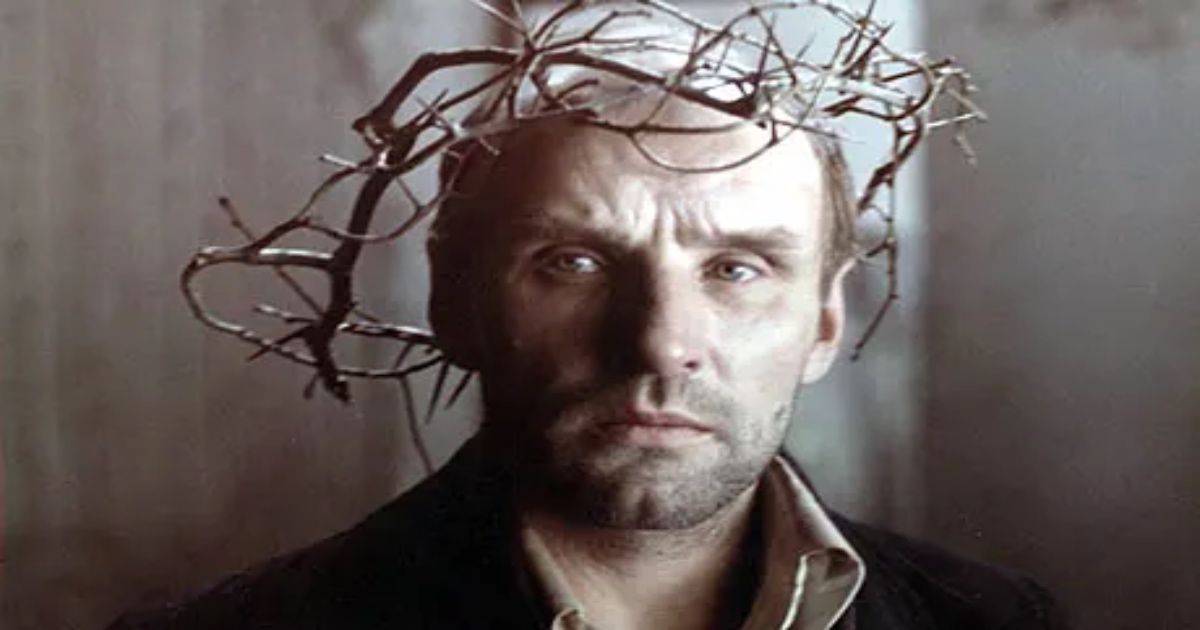

The most radical change in the concept of Stalker occurred after the tapes from the filming of 1977 came out damaged, as the eponymous character went from a tough scoundrel to a Dostoyevskian holy fool, weak and pleading. The leading propagandist of the anti-montage cinema, Tarkovsky wanted not to entertain but to absorb the viewer, for the picture to be disturbing, scary, and a little disgusting, but without any ornamentality and pretentiousness, like a Japanese haiku.

In the end, Stalker became not a cautionary sci-fi tale or a dystopia but Tarkovsky’s take on The Wizard of Oz, a Divine Comedy of the end of the 20th century, undertaking a tourist's journey into the depths of the human spirit, meshing up with saving the world and knowing oneself in the process.

The Meaning of Stalker

To this day, people try to decipher what Tarkovsky wanted to say with this film. From anti-communist and industrialist insights, to religious interpretations, people seem to believe that Stalker holds a powerful understanding of the meaning of life.

Some believe that through the figure of the Professor, Tarkovsky criticizes leftists as walking oxymorons, who cover violence with the pretense of research and create bombs to protect the peace — or shortcomings of the industrialized society that creates all those technologies and artificial limbs, while people keep dying of hunger.

Stalker can be interpreted as a classic cinematic Christian allegory, with the Stalker being a Christlike figure who tries to bring others into faith. He doesn’t ask for anything from the room (the God) because he is happy like a true believer. However, in recent years, Stalker has been viewed through the Zen and Taoist lenses, too.

Stalker as a Spiritual Exercise

The intellectual science fiction masterpiece Stalker can be taken as a koan because the solution to the question here is impossible in the usual, rational plane.

A koan is a paradoxical task given by a Zen master to a student, for example, “Hear the sound of one hand clapping!" In the attempt to solve (or sit with) a koan, the student discovers a sphere inaccessible to the intellect, with its own paradoxical laws. Koans bring one closer to satori (enlightenment, a sudden comprehension of the essence of things-as-such, existing outside our verbal description of them).

Like a Zen koan, Stalker asks a question that can only be answered in another dimension of consciousness. The Stalker lives in a world whose significance cannot be explained or refuted by either logical or psychological arguments. His passion for adventuring towards the Room is irrational. Tarkovsky's film as a whole is a koan as it contains an intriguing riddle but dodges its solution. However, having entered the intuitive-mystical layers of your consciousness, the viewer discovers that there is no riddle in the film. The movie was just a start.

Concerning Taoism, explains Dan Clipca, the Zone symbolizes the human mind, and the characters realize the meaning of life is not in the Room itself but in the process of reaching it, encouraging presence in the moment.

A Cathartic Tragedy

The Stalker tells a story about Porcupine, who had lost his brother in the deathly treks of the Zone and came to the Room to revive him. However, as he came back home, he discovered not his miraculously undead brother but a pile of money. The tragedy of Porcupine is that he realized he is not that great, selfless person he thought he was. His subconscious innermost desire was not to get his brother back but to become rich. Unable to deal with that realization, Porcupine ended his life.

The Writer and Professor realize that they are not ready to deal with their inner demons. The Film Cred writes: “The Zone then becomes a sort of supreme judgment of character that looks into the soul of each wayfarer and exposes their true character”. It is not all grim, though.

As Tarkovsky said: “Stalker is a tragedy, but tragedy is not hopeless. Tragedy cleanses man. I believe that only through spiritual crisis, healing begins.” At the end of the film, Stalker’s daughter, raised in love, shows miraculous powers. She is the hopeful future, signifying, perhaps, that miracles are much closer to us than we think.