The contemporary story revolves decisively around the character arc and hero's journey: the hero is no hero at the start, but rather a troubled figure seemingly incapable of growth, who finds purpose via an unexpected journey. Looking back, stories that influenced Western literature like Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Hebrew, and Norse mythologies (among many), protagonists were here and there flawed, but often unaffected by their calls to change themselves. They were gods, demigods, or functionally identical surrogates, and to claim they were in need of growth was to claim they weren’t at their tallest yet, a general heresy against hierarchical models and real world monarchs who were equally painted to be omniscient.

As we score contemporary stories for similar champions, superheroes have gone from benevolent and titanic to complicated and confused, historic personas have gone from patriotic and infallible to temporally ignorant and prejudiced, and cartoons are less about the almighty Bugs Bunny playing with his food and more about loving oneself and personal growth. In general, our society has lost its adoration for the character who doesn’t need to change in favor of the one who does. With the odd and fun exception of the stoner.

The Stoner as a Paradigm

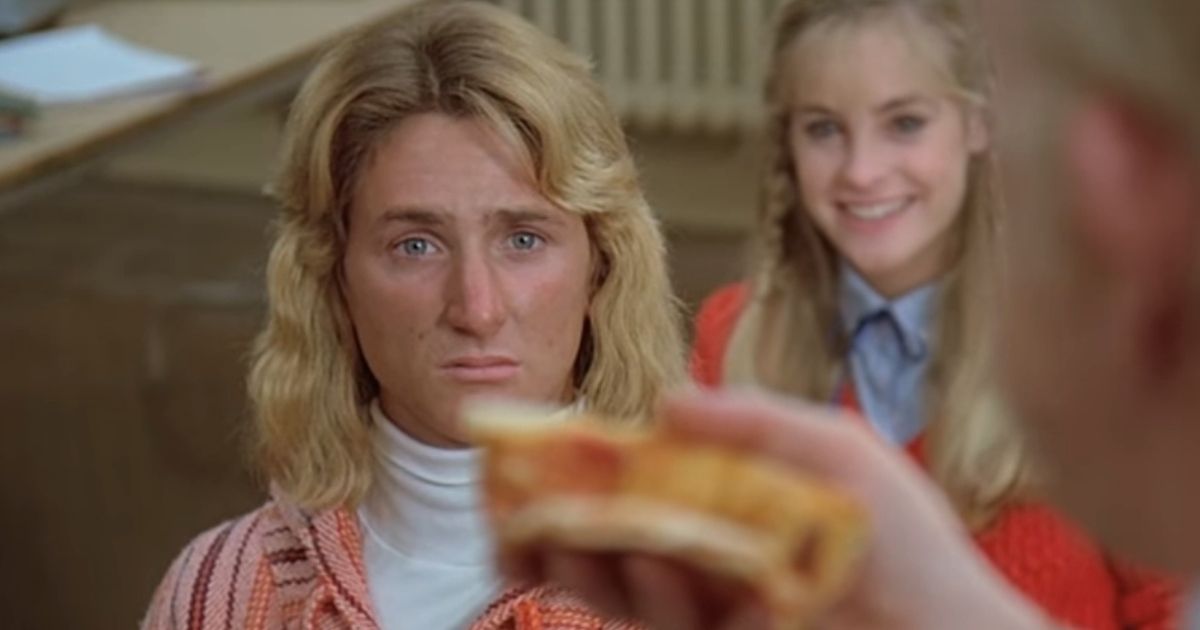

In general, stoner-beloved movies like Bill and Ted and Fast Times at Ridgemont High focus less on how the stoner-esque characters are supposed to grow and more on how they have to fight society in order to stay the same. The protagonists in Friday, Easy Rider, and The Big Lebowski are just trying to get through unexpected plots while keeping their pseudo-squalorly yet satisfactory lifestyles. The stoner character is certain of their anti-status quo purpose yet more or less impossible to destroy or corrupt, like a small and persecuted mythological hero. A Loki, a Coyote, a Cheech or a Chong.

On one hand, the stoner has historically been accepted as yin to corporate yang: stoners are financially insecure, executives are not; stoners are content resting in their financial status, executives are not. If the distinguishing characteristic of the stoner may be their ability to laze, then any conflict involving stoners would be an attempt to move them in some way; the stoner victory necessitates immovability. As corporations have become a more accepted enemy, the stoner's stillness becomes unexpected heroism.

On the other hand, the criminalization of drugs breeds inherent conflict in how the stoner can remain restful while law enforcement demands they be restless — again, Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny, fruitless colonizer and pranking resident. As law enforcement has also become an expected antagonist, the Blues Brothers fleeing the entire National Guard isn’t an umbrellaed celebration of all lawbreaking, but a decrial of the countering corruption and ineptitude. If you’re seeking a grand story critiquing authoritarianism, highlight a civil rights leader; if you’re seeking a small one, highlight a stoner.

The Complications of Stoner Culture

Pausing on the championing of stoner movies, it remains important to note that they're often indefensible champions of patriarchies and rape culture; charming side-steppings from how The War on Drugs is a poorly-disguised, targeted assault on minorities, so the levity of these (often white) protagonists is a form of gloating; or humorless spoofs of drug culture rather than honest and nuanced portrayals. However, when done with equity and intent to disrupt all hierarchies rather than leaving convenient ones in place, the central function of the stoner remains unique and worthy of intellectual celebration, both in how the movies uphold populist traditions of one-dimensional heroes and in how they suggest that the classic stories from which they sprang, now immortal, may have been as well neglected as juvenile by most academics in their runs.

Also, even though protagonists in stoner films are often meant to be beloved jesters and dunces, it doesn’t mean the genre has never had a character arc. Looking at mass market appeals like the Seth Rogen-led Pineapple Express, Dale’s condescension towards his dealer Saul required him to grow more accepting as a person. In Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle, both Harold and Kumar greatly change their lifestyles, Kumar deciding to go to medical school and Harold standing up to his manipulative coworkers. Just as Superman was specifically a boy scout and gradually grew to question grand morals himself, the stoner character can be at first made for a niche market, find mass appeal and recognition, then go from a displayed, marble statue to a clay base for new artists to remold. Heroes die or oversaturate into mediocrity, and the stoner’s grander acceptance bleeds them of counter cultural defiance.

The Future of the Archetype

All this means is that, with decriminalization and cultural maturing, pot flags have the same revolutionary output as taping up a PBR box. The stoner, as they already have in many ways, will lose their lighthearted, love-them-or-hate-them appeal as the persecuted yet content rock. It’s unclear what kind of figure will take their place to continue the long tradition, or that one will even do so anymore. After all, in a society advocating for global egalitarianism for the first time in its recorded history — obviously over the span of a few centuries but nevertheless — there may be less interest in traditionally righteous heroes that maintain faith in omniscience and more interest in complicated and uncertain anti-heroes that exemplify what we all feel in the wake of these changes: nothing is certain and no one seems to know how to be an ideal person yet.

In the meantime, to put on Bill and Ted is in no way a guilty promotion of “inferior art,” but a celebration of the fact that there is none — all art has its purpose, its audience, its merits — and the incomprehensible luck Bill and Ted face in their endeavors can be one viewer’s denialism, another’s magical thinking, and another’s pleasured rehearing of a myth they’d been told a million times, just as ancient listeners did. The stoner movie isn’t retrograde; it’s evolution of a classic format championed by Shakespearean comedies and spaghetti Westerns — easy good guys who are gods in their successes, easy bad guys who are Mr. Bill in their failures, easy stories on the brain. Will the tradition be in vogue forever? Probably not. But that gives all the more cause to enjoy it while it's somehow still hot.