Spoiler Warning: Twin Peaks, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, and Twin Peaks: The ReturnTwin Peaks fans are not ready to let the show go. Amidst (probably false) rumors that David Lynch has a show in development with Netflix and a surprise premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, speculators were quick to wonder if the mysterious projects would return us to the Pacific Northwestern town of coffee, pie, and phantasmagorical horror. The hope that the show might return is not totally unsubstantiated, as co-creator Mark Frost said that the possibility of more remains open, but there are no plans for another season.

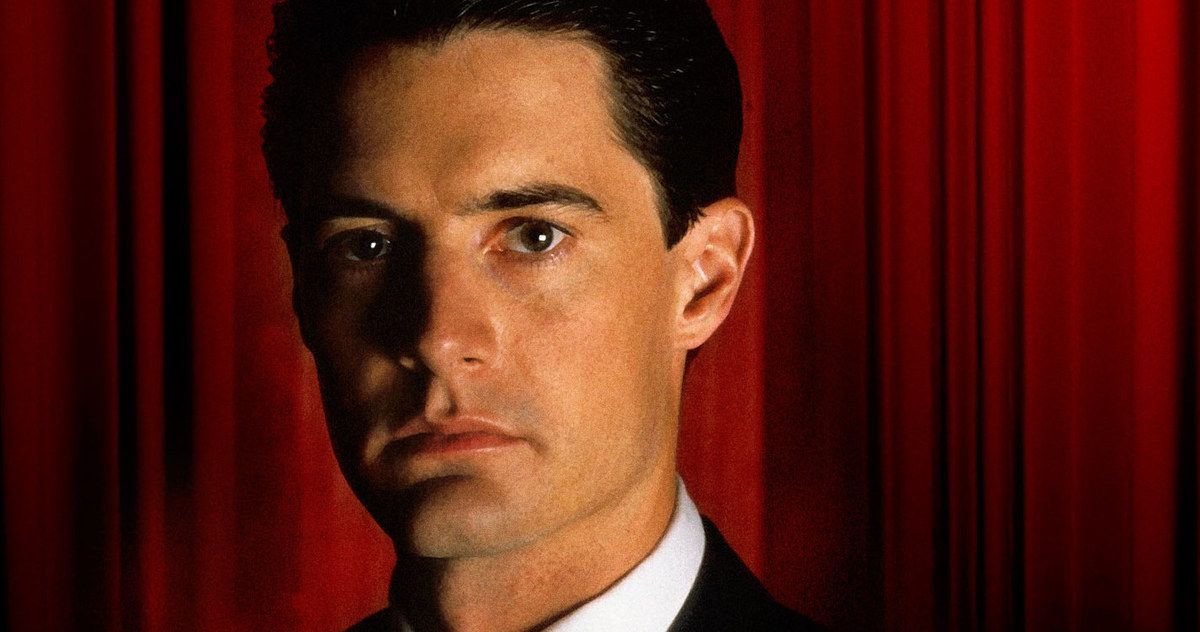

Fans of the surreal soap opera turned horror/noir turned (...whatever Twin Peaks: The Return was) are no strangers to inconclusive endings. Each time the book has closed on the franchise, the final moments have confronted us with ambiguity and cliffhangers: Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) trapped in the black lodge while his evil double roams free; Cooper and Laura (Sheryl Lee) in the lodge witnessing the returned angel; Cooper/Richard and Laura/Carrie outside the not-Palmer house in another world, memories of Laura's former life leading to a blood-curdling scream and a black-out. Our protagonists are always stranded in another world, with no clear way back to our world (i.e., where a yellow light still means slow down).

Despite their inconclusiveness, only the first ending was actually a cliffhanger, an unsuccessful attempt to keep the show from getting canceled. The ending to Fire Walk With Me offered no closure to the series' events, but it was an ending; and despite its poor reception, FWWM could have served as the definitive conclusion. It allows Laura Palmer to breathe in all her contradictions and agony. She is the All-American girl in the grasp of a great evil at the core of her home, family, and existence. That evil overwhelms everything, symbolized by the disappearance of the angels. In the end, she cannot save her life -- but she does save her soul, refusing to participate in BOB's cycle of abuse and secrecy.

The film (and ostensibly the franchise) ends with two lost souls, Laura and Cooper, previously separated by time and death, both having "failed." Cooper could not cure Twin Peaks of the evil under its surface, and Laura could not survive or reconcile her duality. Yet both have failed nobly as forces of good. They cannot bring the angels back to the real world, but they are greeted by their own angels in the next world.

It's a meaningful ending but not a satisfying one (unless you're willing to think about it). Luckily for fans, Twin Peaks returned in time to fulfill its twenty-five-year prophecy and answer everyone's burning questions.

And it almost did -- until it left us on that dark street, familiar and unfamiliar, with a final cry of anguish. It is not the happy ending many had hoped for, which is why many still hope for more. Still, it is the perfect ending, the one staring fans in the face since the beginning, even in its initial incarnation as a quirky show with moments of the bizarre and horrific.

Below we'll take a look at the ending of the franchise in the context of its overarching story, themes, and meta-text to examine how the conclusion surmises everything the show was about (in so much as the show can be said to be about anything).

Surmising the Unsurmisable: The Story

To surmise Twin Peaks in full is impossible. There are so many intersecting threads, twists, and characters, and anytime a storyline is resolved, it hydras into a series of new mysteries. The world of Twin Peaks is a wavering TV station, a wall of static tuning into disparate signals as they pass by, trying to form a cohesive story. Still, there are definite throughlines.

Twin Peaks is the story of an all-American town turned upside down when prom queen Laura Palmer is murdered. The investigation, led by the charmingly peculiar Agent Cooper, reveals a network of secrets and conspiracies beneath the town's surface, as well as supernatural mythology that influences its populace. Cooper is moved by the community's warmth and seeks to save it from the darkness it is brewing.

We learn that Laura was raped and killed by her father, Leland, under the influence of the entity BOB (Lynch being a master of contrasting black and white Americana morality with ambiguity, the fact of the possession never removes the blame from Leland; it contextualizes his abuse and inner conflict in mythical terms). Leland dies from self-inflicted head trauma, and the case is solved. The quirky lives of the Twin Peaks residents continue on.

Cooper gets caught up in a game of cat and mouse with his evil former partner Windom Earle, who comes to Twin Peaks to harness the power of the Black Lodge. Earle finds a way in, Cooper follows him, Earle is killed by BOB, and Cooper's evil doppelganger escapes into the real world. Cooper is trapped in a timeless limbo, where he greets a newly dead Laura Palmer.

Cooper's double, now known as Mr. C, spends the next twenty-five years raping, killing, and undoing all the good Cooper had represented. Though his motivations are never fully elucidated, Mr. C seeks coordinates to reach the mother of all evil, Judy. Coordinates that, of course, lead him to Twin Peaks. When Cooper finally returns (after much, much delay), he meets his shadow for a final confrontation.

Throughout The Return, we see that Twin Peaks is in decay (as is the rest of the country, though the implication throughout the original series was that Twin Peaks seemed untouched by the larger disintegration of American values that was already happening). Its inhabitants are trapped in the same patterns, and the darkness that was under the surface has made its way to the forefront.

The audience desires to see Cooper return order. For one glorious moment, our dreams are realized: Mr. C is shot, the essence of BOB is literally punched into non-existence, and everyone celebrates a job well done, all under Cooper’s team-oriented direction. This, at last, seems to be the showdown between good and evil fans had hoped for. Cooper then travels through time to save Laura from her death, preventing the event that took away the town's innocence.

The only problem? There is another hour in the runtime that celebration after the Marvel-esque final fight features an eerie superimposed image of Cooper in close up, reminding us that we "live inside a dream," and Laura is swept into the unknown just after her rescue.

To save Laura once and for all, Cooper travels into an alternate reality, where he becomes "Richard," a man that mostly resembles good ol' Coop, plus flashes of Mr. C's brutality. "Richard" finds Carrie, a middle-aged woman who looks exactly like Laura Palmer. He decides to bring her home to Twin Peaks, and Carrie (one of Lynch's archetypical women in trouble) has little choice but to go with him.

This leads us to that ending. Sarah Palmer never lived in the house. Cooper doesn't know where he is. "Carrie" hears her mother's voice and screams, and all the lights disappear.

How did everything that came before lead to this strange dark street? This can best be understood by analyzing Cooper's goals throughout the series. What Cooper really wants is to save Laura from her fate — and, by extension, the town of Twin Peaks. At first, he attempts this figuratively through investigation — if he can explain Laura Palmer’s death and arrest the guilty parties, he can put her soul to rest. Except the answer to her death is so strange and horrifying that it lands him in a deeper mystery that leads to his lapse into non-existence and the reign of his shadow. He returns to a world that is falling apart.

So Cooper, formerly respectful of the forces beyond comprehension, does something very un-Cooper (though in line with his motivations and usual charm) -- he plays god. No longer satisfied to investigate and understand, he returns to what he sees as the root of Twin Peaks' sickness, and he undoes it. This attempt to resolve things simply is what lands us on that dark street.

We are not used to seeing Cooper be wrong, be truly lost. Nor are we used to the moral ambiguity we see in him as Richard. We are so accustomed to Cooper as an uncomplicated force of good, capable of resolving the innocence of Twin Peaks and the darkness that plagues it, that we are unwilling to see him as reckless, unhinged, irresponsible — but his journey to “save" Laura is all of these things and more.

Laura may no longer die, but the events that led to her death still happened. The illusion of innocence and peace in Twin Peaks can last longer, but it is still an illusion. In trying to "cure" the town by removing the catalyst for its self-reckoning, Cooper -- the man who once saw through the veneer of Twin Peaks and loved it anyway -- succumbs to the world of glossy surfaces, swallowed by the darkness they cannot contain.

Making Sense of the Nonsensical: The Themes

There are many themes that run through Twin Peaks: the ineffable, duality, the American Dream vs. American Decay, and the effects of industry and consumerism on everyday life.

The most general thematic reading of Twin Peaks is as a story of the ineffable -- the incomprehensible forces that dictate our lives. What happens when we try to understand our multifaceted reality? Can we? Does this search for comprehension lead us to a better future, or does it knock the lid off the darkness that should not be touched?

Duality is explored extensively -- in the show's title, Cooper's two (four?) selves, Laura's double life, the Black and White Lodges, and doppelgangers. Over and over, the show asks us: how can these double things be? How can Laura be the heart of the community and its victim? How can Twin Peaks harbor so much innocence and so much evil? Can these forms resolve their duality (preferably with whatever is "good" coming out on top)? Will their duality destroy them? Where the series began with a balance of light and dark, by the time we return to its world, the darkness has gained the upper hand.

Lynch has always had a fondness for surreal Americana, and this pet theme is explored throughout Twin Peaks. Despite taking place in the nineties, the original series feels timeless, hearkening back to an idealized image of post-war American Life. This vision of 1950/60s sleepy living is a popular point of nostalgia, particularly in contrast to the violent dissonance of the modern-day. Of course, this rosy impression of America's past harbors a horrifying history, and Twin Peaks illustrates the darkness beneath the Norman Rockwell surface.

The thematic question that runs through Twin Peaks is related to the narrative question (who killed Laura Palmer?) -- what brought on this sickness? Was it internal or external? Has something polluted the American Dream, or is there something rotten in the Dream itself? Nostalgia plays a major part in this, be it the yearning for an America that seemed prosperous or a time when Laura Palmer was alive, and things seemed good.

Twin Peaks is a small lumber town, a town of local industry. That may change, however, as plots to buy the wood mill and hyper-industrialize the town are introduced in the first episode. This corporate greed would displace the inhabitants and what they built -- but it would also be the next natural step in a town dedicated to the industry. The wood mill is already cutting the forest down, albeit slowly; corporate interest would merely push the process along. By The Return, this process has run its course: the chic little diner has become a franchise, the town's inhabitants have to sell blood to afford a meal, and its youth are lost in a world of drugs and stuff. There is a sense of displacement.

The supernatural forces are associated with industry/consumerism. They are said to live above a convenience store and were brought into this realm by the nuclear bomb, that terrifying symbol of the cost of America's post-war prosperity. The Black Lodge entities influence humans into evil in exchange for garmonbozia (pain and sorrow), which can itself be interpreted as a metaphor for capitalism or the manner in which our inner lives are manipulated by advertisements, politics, and addictions (if you need to wring concrete meaning/politics out of this elusive story). Here we have the duality of American life and values: liberty and happiness vs. corporate interests and oppression. Are they opposing forces or two sides of the same coin?

Got all that? Okay. All of these themes come to a head in the series finale, which is a counterpoint to the final moments of Fire Walk With Me. Where that film ended with Cooper and Laura as redeemed figures despite (actually, because of) their noble failure, The Return ends with an apparent victory (the "rescue" of Laura) that leaves them in a hopeless void. Though much of the show deals with forces beyond our control, we arrive at both of these conclusions because of the choices our two protagonists have made.

As mentioned above, Cooper disrespects the unknown in the series finale. When we first meet him, Cooper is a force of curiosity and awe, with a strongly defined moral compass that keeps dark forces from manipulating that childlike wonder. Cooper (who isn't really Cooper, which we'll get into in a second) has been gone too long by the finale. He cannot recognize the world and no doubt blames himself for its ruin. In choosing to provide a "happy" ending for Laura, Cooper forgoes the openness to complexity and mystery that made him great. He has become reactionary, a reductionist.

This attempt to operate in black and white terms is made especially fascinating by the character that carries it out, the mysterious Richard. Richard can be viewed as a reconciled duality. He is both Cooper and Mr. C. The problem is that Richard does not see himself as an ambivalent figure. He sees himself as Cooper, a good man with a righteous quest. He, therefore, has no qualms about disrupting the world around him in an effort to get "Laura Palmer" home -- even though Laura Palmer doesn't really exist anymore, and he has only the haziest idea of what he hopes to accomplish. In a way, Richard is more disturbing than Mr. C, simply because Cooper's shadow is predictable in his own way. We know how he operates in the world.

The same is true for Cooper, yet Richard is mildly unpredictable to himself and the audience. He is more conflicted than Cooper or Mr. C because he is both and neither. When Audrey comes on to Cooper in the first series, Cooper gently rebuffs her advances and says that what he wants and needs are different (thus illustrating Cooper as a man of principle). Early in The Return, Mr. C declares that he doesn't need anything -- he merely wants (thus illustrating Mr. C as a man of base impulses). Richard has the unfortunate duty of wanting and needing, and who knows which impulse it is that brings "Laura" home.

Where a protagonist and antagonist can safely engage in their mythic battle of opposites, real people cannot be reduced to one or the other. Much of the real world's garmonbozia can be attributed to this reduction.

Richard/Cooper's "solution" to his and Laura/Carrie's displacement in this reality is to bring Laura home, to return her to a cozy American dream of childhood she was denied. But home is where the trouble began. The abuse Laura faced at the hand of her father was not separate from the structure of her nuclear family. BOB was not an evil preying upon the otherwise perfect small town. The evil is part and parcel of the nuclear family; it is the misogynistic, racist, imperial ideology woven into the wholesome-seeming ideal. This does not mean that elements of that ideal are not beautiful — only that they are inseparable from ugly realities.

Twin Peaks ends with a failed homecoming because it was always about the draw of the past and the impossibility of returning. Laura Palmer cannot be resurrected, nor would resurrection remove her excruciating experience. If the present seems horrific, the remedy is not the past: the seeds for where we are now were planted then.

The answer cannot be a reduction, forcing things back to the way they once were. This is true for the story of Twin Peaks, and it is true for our understanding of the show and the world. Everything is too mysterious, beautiful, and horrible to be broken down into black and white, even if closure and comprehension are what we desire. We cannot be faulted for this desire; it is hardwired into us. A major function of the arts is to provide catharsis for a reality that is chaotic. This is especially true of popular media, which creates catharsis by putting forward narratives with clear themes, formulas, and resolutions. This serves a human need -- but we also need honesty and ambiguity, no matter how painful.

Formalising the (Nearly) Formless: The Meta Text

It may seem strange to conclude with an analysis of Twin Peaks as a self-reflective piece of media rather than the universal implications of its themes. Still, the impact of these themes results from the deconstructive approach the franchise takes to formula and genre. One of the earliest pleasures of Twin Peaks was the impression of tuning into commercial television and seeing a portal into another world. It wasn't simply that the program was made with more artistic integrity and vision than the majority of TV at that time (though it was, and it changed television forever). It was the sense of the genuinely occult, the idea that the safe images of the idiot box could tap into something deep in our psyches that we must confront. This is the overarching power of Twin Peaks -- to shock us with the sublime after drawing us in with the rote.

The show's first incarnation is a soap opera and police procedural (it calls attention to its own trappings as a soap with the in-universe show Invitation to Love). The show distinguishes itself from both genres in key ways. Despite the camp and bizarre plot twists it shares with soap operas, Twin Peaks is able to imbue its cartoonish characters with genuine pathos and complexity. While most police procedurals begin with a murder whose human impact takes a back seat to the investigation, Twin Peaks never loses sight of Laura Palmer or the genuine trauma her murder was for the town's inhabitants.

A major complaint of fans when David Lynch released Fire Walk With Me was about the lack of quirkiness. The coffee and pie? The small-town hijinks? Why is everything so horrifying? A strange question to ask after the show's central mystery is revealed to center on domestic violence, rape, and incest. But it was an early indication of the paradox of what Twin Peaks would become -- a show that drew us in with the hum of something deeper beneath the formulaic exterior, but that pissed us off when that hum of something deeper eradicated the surface.

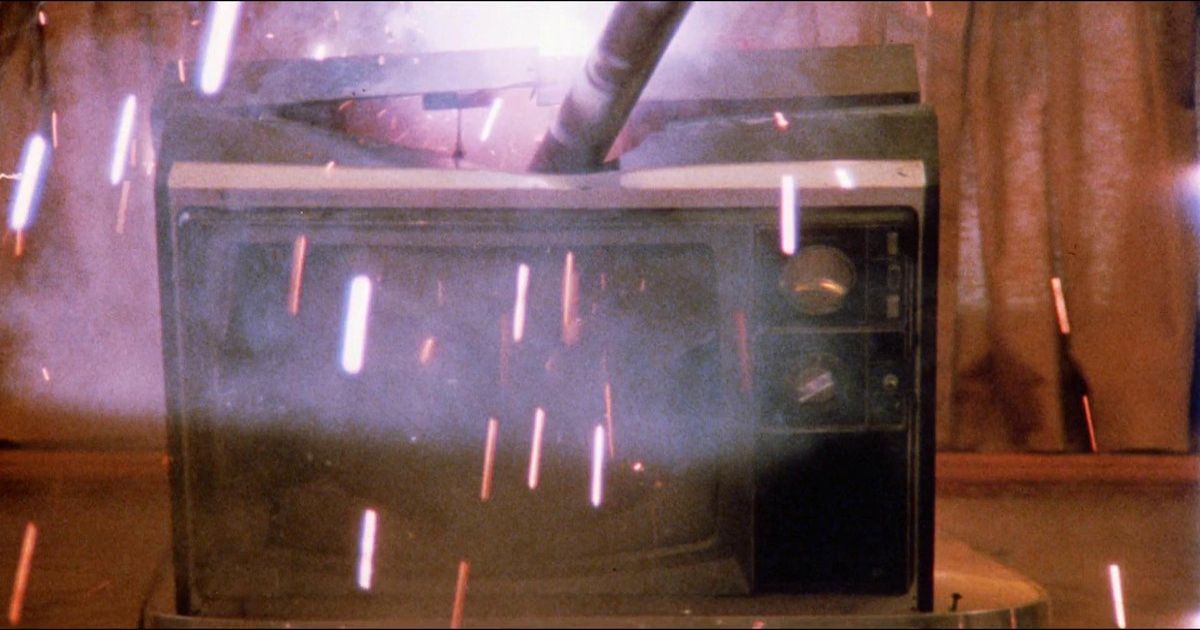

Even if we love the show for deconstructing the ramifications of televised storytelling, we still want what that storytelling promises: closure, resolution, and good triumphing over evil. The film begins with the destruction of a television set to let us know that we have left the world of soap operas and police procedurals (though both factor into the film in a warped, not-so-fun house reflection of the original show): we are in the ambiguous, R-rated, phantasmagorical world of a David Lynch film.

The fact that fans hated the ending of Fire so much is both ironic and extremely important to understanding The Return's finale. As we discussed at the very beginning of this article, Fire Walk With Me could easily have been the end of Twin Peaks and would have been the closest thing the series could produce to a happy ending. The desire to be good, personal strength, and a refusal of hatred prove to be the only salvation, not in the mortal sense but in the spiritual sense. It is the answer to our duality, to the sickness hiding in our world. We cannot force the world to make sense. We cannot force the angels to return. They may never have been here in the first place, but we can find our own sense of peace, truth, and love.

This is not what some fans wanted. Some fans wanted the angels to return for real and to lay bloody waste to the forces of evil. In other words, they wanted simplicity and resolution, two things Twin Peaks never provided. This counterintuitive desire and a media landscape full of hollow nostalgia and blockbuster morality tales birthed the return to Twin Peaks.

The Return is a mishmash of media forms that were prominent at the time of its release. The morally ambiguous anti-hero (e.g., Tony Soprano, Walter White, and now Mr. C), who embodies the ambition and ruthlessness of modern American culture. The superhero film (mostly in that final showdown), which embodies morally superior forces that triumph over morally inferior forces. And the nostalgic revival (e.g., Fuller House), which appeases our hunger for a simpler past by regurgitating characters and stories from older IPs. These media forms are honored in the revival's first "ending" before being challenged by its real conclusion. Mr. C meets a grisly end (as all anti-heroes in tales of ambition must), the essence of BOB is punched out of existence (translating morality into terms of physical strength), and the show's long-absent protagonist reunites with many of the characters we loved from the first show in a familiar setting (a return to the comforting past).

The problem is, this isn't real -- none of it. Not just in the sense of being fiction (though there is that), but this ending isn't true. It satisfies what we want but not what we need. That's why Cooper's face is superimposed over the victory lap. Without it, the scene simply wouldn't work. With it, it takes on a creepy ambiguity that never lets you really believe the scene. It's a mental fabrication. This is not to say that all of Twin Peaks is Richard's dream or Audrey's dream or anything so concrete -- only that it isn't real to begin with, and when it is reshaped to fulfill our impatient desires, it becomes not only unreal but false.

Twin Peaks can tolerate being unreal -- it's what allows it to tap into the transcendent. But false? It would rather turn its long-time fans against it than do them the disservice of giving them exactly what they want. To illustrate this, it does give us what we want and then shows us our desire's destructive potential.

Twin Peaks has always delighted in subverting our expectations (represented by the media formulas the show follows and destroys) — it just used to do it in a way that was more fun. But after you’ve revealed that your central mystery was about a father assaulting and killing his daughter while the broader community contributed to her demise in so many ways, big and small, direct and indirect; after your protagonist has played god to shape the world to his idea of justice — well, you may no longer be in the position to fixate on the cozier elements of your world. Those elements are still there, and they still mean something, but the darkness cannot be separated from them. It must be dealt with. It may be time to face it head-on, even if all we can do is feel the full breadth of our trauma and wail.