Film adaptations often bear a precarious relation to their source material. The fact of the matter is that literature and motion pictures are very different art forms, and the translation of stories from one to the other requires much reshaping. Rare is the adaptation that matches or transcends the quality of its source. A film can be so faithful to its source material that it fails to create its own experience; or it can divert so much from the original story that the only thing they share is a title. In either case, the weight of a preexisting intellectual property is a burden, one frequently too much to bear.

Some films forgo the traditional adaptation process altogether. They are intrinsically linked to a prior work of literature, but they take whatever is cinematic and effective about that material and rewire it into an original film. Sometimes the source material is merely a jumping off point, or the source of thematic ideas explored with a different story; sometimes it is a work that grounds an otherwise untenable film in a familiar framework; and sometimes it is a straight-up rip-off with a different title and character names, made with the hope that the author's estate won't notice (they almost always do). In any case, these films represent a fascinating threshold between the literary and filmic forms, depicting the way meaning in one can be optimally reconfigured for another.

5 The Fly (1986) / The Metamorphosis (1915)

David Cronenberg's The Fly is officially an adaptation of Kurt Neumann's 1958 film and George Langelaan's story of the same name. All three versions focus on a scientist whose experiment-gone-awry transforms him into a man/fly hybrid. While the remake doubles down on the ickiness of the story's previous incarnations, it is less concerned with the nuclear era's "man tampers with nature" theme. Cronenberg's body horror is defined by psychological precision and gallows humor, and his version of The Fly reaches for more than shock and cultural hysteria. He is interested in the tense relationship between mind and flesh, and for inspiration he turned to a different tale of transformation: Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis.

Kafka's fiction is characterized by casual absurdity, inscrutable forces, and individuals locked out of the processes that determine their fates. The Metamorphosis is the crown jewel of Kafka's fiction, a fever dream of industrial alienation, angst, and the loss of self. The story follows Gregor Samsa, a traveling salesman and the primary provider for his family, who wakes up one morning transformed into a massive insect. Unable to work (or communicate), Gregor's family comes to regard him as a nuisance. Deciding he is more trouble than he is worth, Gregor curls up and dies. No explanation for Gregor's transformation is provided, and while the characters regard it as unusual, it is not the crime against nature that the doctor's transformation in The Fly represents. The reader is encouraged to take the story's dream logic as allegorical. Gregor's metamorphosis can be interpreted as the dehumanizing effect of industrial capitalism (as soon as he is unable to provide for his family, he is regarded as a burden). It can be read as a tale of depression and alienation (Kafka was a noted depressive, and the guilt complex and withdrawal Gregor experiences parallel a mental health crisis). Or, as Cronenberg describes in his Paris Review published essay The Beetle and the Fly, Gregor's transformation can be taken as a metaphor for aging: just as Gregor wakes up to find his body (and eventually his mind) unrecognizable, every human lucky enough to reach old age transforms into something they do not identify with: decay.

Given the film's era (and Cronenberg's fixation on the consequences of transformation in the context of a romantic relationship), The Fly was interpreted as an AIDS metaphor upon release. This is a valid interpretation, but the doctor's transformation taps into human anxieties about any kind of bodily disintegration, and what that says about our spiritual condition. Where the original film finds horror in what is distinctly non-human, Cronenberg's film is attuned to what is universal about its central transformation. In that sense, its spirit is closer to Kafka's tale than to its own source.

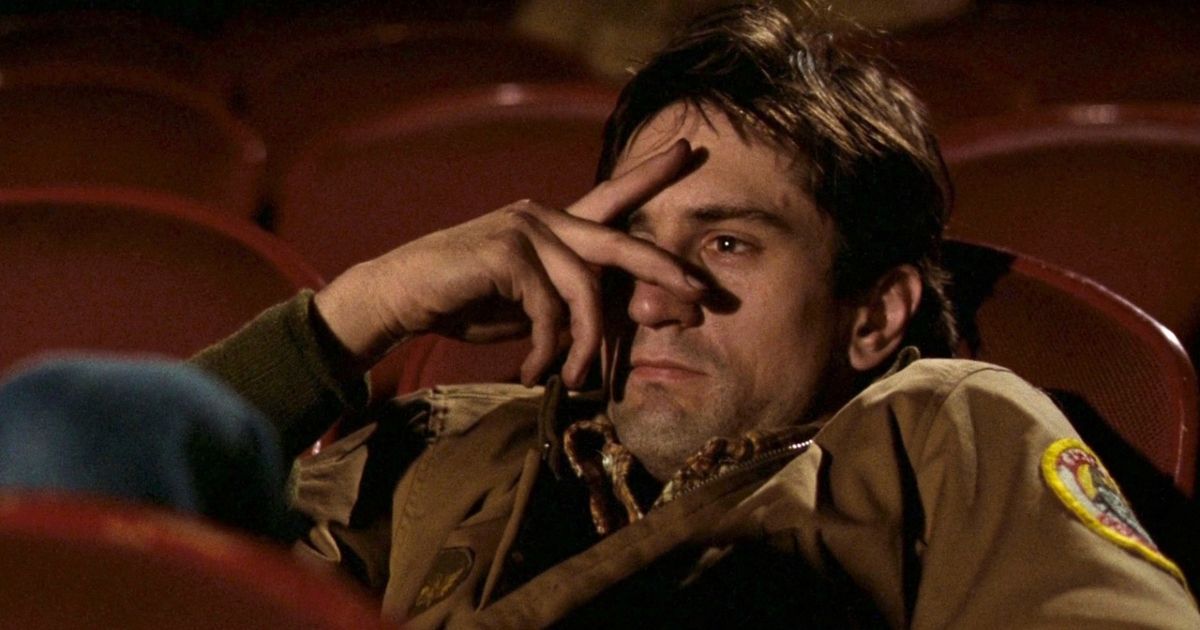

4 Taxi Driver (1976) / Notes from Underground (1864)

Consciousness is an enormous burden, particularly in isolation. The nameless protagonist of Fyodor Dostoevsky's novella Notes from Underground has entered a state of self-imposed social withdrawal by the time he writes his eponymous notes. An educated former civil servant, the man writes a diatribe against civilization, rationality, utopic thought, education, the reader, and himself. The novella is in two parts: the first in the present as the man explains his retreat; the second in the past as he furthers his descent into psychological isolation. Dostoevsky includes an author's footnote explaining that the man is the type of person who must develop given the changes in Russian society. Critics have taken this as a reference to the intellectual threshold an educated man like the protagonist would have lived through: Russia's Western-imported enlightenment (full of rosy ideas, e.g. man as a "noble savage" who would behave decently if given the proper structure) was turning into a cold Utilitarianism (focused on rational egoism). The underground man takes issue with both. He has found his head filled with ideas that have alienated him from himself: contradictory social philosophies occupy his mind, and he rejects them all. Even as he uses language to explain himself, he claims that words are the enemy.

The protagonist of Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver is a similar festering loner, though Travis Bickle is as American as the underground man is Russian. A poor Vietnam vet with insomnia who drives a cab, Travis drifts through the nightmarish New York streets, at once repelled by the world he sees and very much a part of it. Screenwriter Paul Schrader wrote the script while living in isolation in Los Angeles. After experiencing persistent pain in his stomach (not unlike the underground man's aching liver), he went to a hospital - and realized that he hadn't spoken to anyone in weeks. "[...] It occurred to me," Schrader said of the incident, "that what I had become was like a taxi driver -- a man who was locked in this iron coffin in a nightmarish world that he was inventing. When that metaphor occurred ot me, it was relatively simple to find a plot that would adhere to the psychological reality."

Like the underground man, Bickle finds his idea of the world at odds with the world he sees - even though the way he sees it is his own mental construction. Where the underground man's dysfunction manifests in his futile attempts to match the ideals of great literature, Travis' descent into vigilantism and near assassination is closely linked to America's gun culture and its lone cowboy archetype. Both men attempt to find righteousness through the oldest literary trope in the book: the redemption of a prostitute. Where the underground man's inability to live up to this narrative causes him to retreat deeper into the underground and inaction, Travis takes drastic, violent measures - and proves society as sick as him when the world above praises his actions and "delivers" him from the underground.

3 The Lion King (1994) / Hamlet (1603)

The Lion King's famous relation to Shakespeare's Danish tragedy is ironic, given that it is technically Disney's first non-adapted animated feature. The relation is also arguably overstated: there is no shortage of drama fixated on royal turmoil and infighting. In fact, the conflict wasn't even going to be between the lions at first: the original story meetings for the project proposed a tale of extra special warfare between lions and baboons. The writing team settled on "the structure of [...] a dramatic journey from childhood into inheritance and responsibility, presented on an epic scale and leavened by musical comedy." Hamlet could be described as such (minus the musical comedy); but so could a thousand other stories. It wasn't until the action was scaled back to a single pride and the duplicitous character of Scar was introduced that the writing staff took note of the parallels. Screenwriter Irene Mecchi was known to refer to the film as "Bamblet," a combination of Bambi (1942) and the Bard's tragedy.

Despite the rocky road to the film's status as a spiritual adaptation, there are many parallels to the play and a few references (the most obvious of which is Scar idly playing with a skull). Both stories track youth forced into maturity by a familial betrayal, and a quest for revenge taken on begrudgingly. Like Hamlet, Simba is motivated toward responsibility by a vision of his father's ghost. Of course, there are just as many divergences. Simba witnesses his father's death and spends time in hiding (in this sense the story is closer to the recent Viking epic The Northman, which takes inspiration from the same legend as Shakespeare's play); Simba never feigns madness; his mother's relationship with Scar is clearly coerced and desexualized; Nala doesn't commit suicide; and Simba's choice to take action comes just in the nick of time, allowing a happy ending for all but Scar. That ... isn't how Hamlet ends.

Given the looseness of these parallels, it's a bit surprising that The Lion King has been identified as an unofficial Shakespeare adaptation to such an extent, when there are countless other films that parallel the Bard's plays. The overt association with Shakespeare in the public consciousness can be attributed to the film's unusual weight. While most classic Disney films contain much depth and sadness, the majority still operate within the framework of a fairytale: their dark imagery and orphaned characters reflect a "once upon a time" sheen that is comforting. Despite its talking animals and musical numbers, The Lion King is structured like a tragedy - albeit one with a happy ending. Where Hamlet's fatal flaw is indecision, Simba's is irresponsibility. This being a Disney film, Simba comes to learn responsibility and everything works out; but until then, the character is wracked with the same conflict, guilt, and avoidance that defines Hamlet. Though the stories end in drastically different places, the themes of their journeys are quite similar. Which, given that one is a benchmark in world literature and the other is about an emo lion with a farting warthog friend - is impressive.

2 The Master (2012) / V. (1963)

Thomas Pynchon's V. is a tale of Western civilization's descent into the inanimate and a dialogue between modernism and postmodernism. Jam packed with digressions, paranoia, and history, V. is grounded by two vastly different but interrelated characters. One is Herbert Stencil, the middle-aged son of a spy who seeks the mysterious V. referred to in his fathers' journals; a woman who reappears throughout modern history at times of political crisis. Stencil's quest for a unifying narrative to explain the evils of the twenty-first century is in line with the philosophical aims of modernism. On the other side of the equation is Benny Profane, a discharged Navy sailor wandering aimlessly across the East Coast who Pynchon describes as a schlemiel and human yo-yo. A bumbling ne'er-do-well who never changes, Profane's inability to match the tenets of growth and motivation demanded by traditional literary conventions makes him a comical figurehead of postmodernism. Profane and Stencil fall into orbit around a New York pseudo-Bohemian group of "intellectuals" called the Whole Sick Crew, and though the two are polar opposites, they are identical in one key way: the extremity of their world-views means they are unable to find meaning.

V. is probably unadaptable - which is a shame, because many of its vibrant incidents and characters jump off the page, movie-like. The chapters in which unreliable narrator Stencil questionably reconstructs historical events to prove the existence of V. would be challenging to realize visually, but they are populated by so much dazzling imagery and drama that the mind reels at the filmic possibilities. Luckily, fans of the novel eager to experience its pleasures on the big screen, can turn to Paul Thomas Anderson's examination of postwar malaise and soul-searching, The Master. Though far less faithful to the novel than his official Pynchon adaptation, Anderson's film borrows many of its key themes and elements from the author's debut. Like V., The Master follows a drifting veteran (Freddie Quell, played by a feral Joaquin Phoenix) in post-war America who is unable to find a place for himself; that veteran becomes tentatively involved with a cult-like group with dubious answers to the twentieth century's spiritual questions; and all the while the veteran's nihilistic bestial nature is contrasted by an eloquent man with a grand unifying theory, who nevertheless is the veteran's spiritual twin.

Though he swaps Pynchon's paranoid quest to reveal Western Civilization's deadly muse for a blossoming new-age religion modeled loosely after Scientology, Anderson is fixated on the same major themes that populate V.: the inscrutable tides of history, the alienation of the common people swept away by those tides, and the efforts to comprehend the violence and dispossession of the twentieth century (and modernity in general) through metaphysical frameworks at once profound and utterly meaningless.

1 Nosferatu (1922) / Dracula (1897)

One of the most famous instances of plagiarism in cinema is also one of the most influential silent films of all time; and because of its precarious relationship with unlicensed source material, it was almost lost entirely. F.W. Murnau's German Expressionist classic Nosferatu is the first screen adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula - but because the rights to the novel could not be secured, efforts were made to distance the film from the novel. The names were changed, the story retitled, the monster reshaped; ultimately to no avail. Despite the film's substantial success upon release, the Stoker estate successfully sued for the destruction of all existing film prints. Thankfully, some survived and were later restored, allowing its already substantial influence to grow, cementing the film's status as one of the greatest of the silent era.

For all its trouble with the Stoker estate, Nosferatu does make alterations to its source material deeper than the cosmetics. It popularized the notion of the vampire killed by sunlight (the original Dracula may not have sparkled, but his aversion to vitamin D was not fatal). Where Dracula is elegant and seductive, Count Orlok is ghastly - his appeal thus clearly becomes the psychological power he yields. The shift in setting makes for a film that is steeped in German nuance. Like many of the German Expressionist horror films, Nosferatu taps ambiguously into the cultural anxieties and despair of a nation deep in a depression and gradually coming under the spell of Fascism. Whether its central ghoul is an antisemitic symbol or a symbol of antisemitism (i.e., an embodiment of the oncoming Nazi threat) is debated to this day, which speaks to the movie's ability to tap into the nightmares of the time without presenting a fixed meaning.

While the most iconic image of Dracula is still Bela Lugosi's turn in Universal's 1931 adaptation, Max Schreck's turn as the vampire is a monster perfectly suited to celluloid; his boogie man appearance lunges right off the screen, and his realm of shadow can only be defeated by the confrontational power of light. The film would not have existed without Stoker's novel, and the choice to pursue the material illegally caused much strife - but the circumstances made Nosferatu much more than an adaptation of a book. It became a nightmare on film stock that was all its own; and ultimately the film (and cinema) is all the better for its unofficial approach.

.jpg)